The Joy of Belonging: What Marathon Fans Teach Us About Human Nature

Issue 187: Today over a million people are cheering on the NYC Marathon runners. We explain why we cheer on strangers.

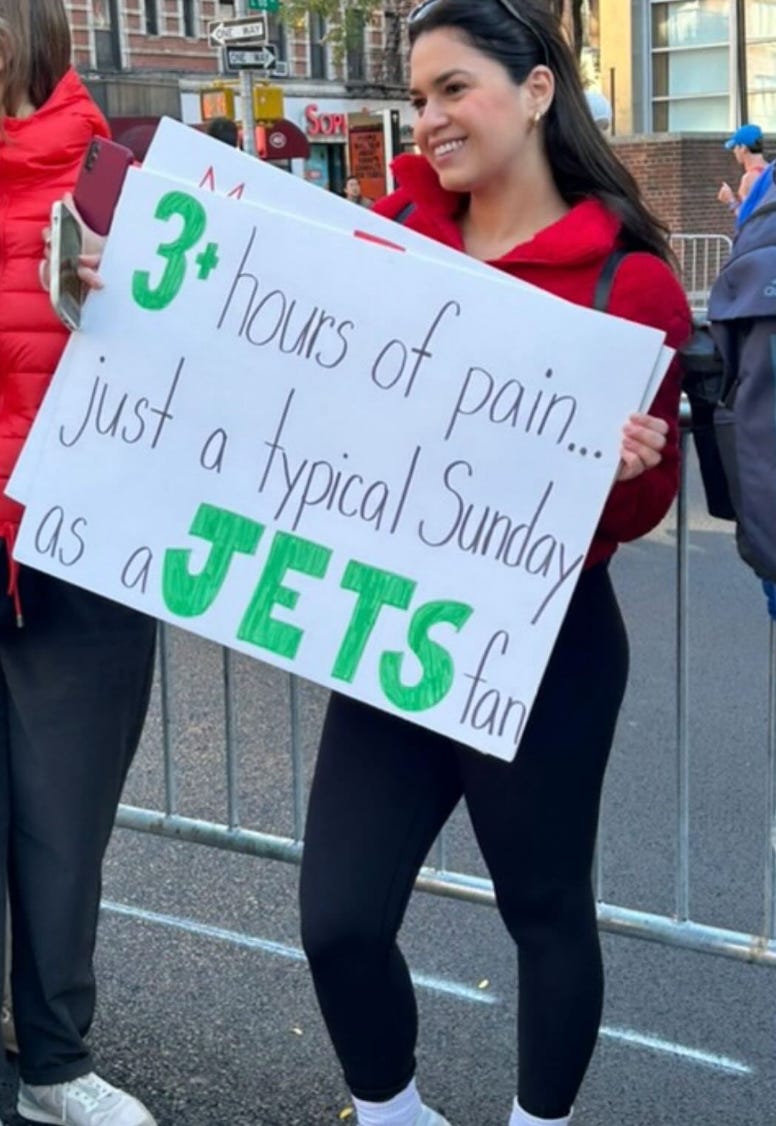

New Yorkers are famous for having no time, no patience, and definitely no interest in small talk with strangers. But today, over two million are expected to line the streets, yelling, clapping, and high-fiving sweaty people they’ve never met. It’s the NYC marathon. Some came to support their family or friends, but before long, nearly everyone in the crowd finds themselves enthusiastically cheering for strangers.

Back in 2022, Dr. Anni Sternisko, was one of the runners. She recently spoke with the New York Post about her experience and why New Yorkers would spend their precious Sunday rooting for strangers. She explains the strange psychology of fans below:

The overview: Why do we cheer even for total strangers?

There are many reasons, but let’s unpack four of them in more detail.

The marathon turns strangers into teammates

We love social rituals

Cheering together connects us

Supporting the runners feels good

The marathon turns strangers into teammates

When we identify with a group—our nation, our football team, our city—that group becomes part of our social identity, part of who we are. And you will also know that we are wired to divide the world into “us” and “them.”

But when the marathon rolls around, something interesting happens: the boundaries of “us” expand. For a few hours, tens of thousands of sweaty strangers running past us suddenly feel like part of our group.

This happens because our social identities are flexible. Psychologists call this social identity complexity: We belong to many, often overlapping, groups and which one matters the most depends on context.

In one set of studies, Jay and his colleagues assigned participants to mixed-race teams (the “Lions” or the “Tigers”). Once participants started to think of themselves as members of these teams, racial biases dropped. Why? Because participants racial identity faded into the background and gave way to a new, shared team identity that transcended other group boundaries.

Sports can create the same kind of inclusive social identities. When researchers reminded Manchester United (U Man) fans of their team allegiance, they were less likely to help an injured stranger wearing a Liverpool jersey rather than a U Man one. But when researchers prompted U Man fans to think of themselves as “football fans”—a broader, more inclusive social identity—that bias disappeared.

Something similar is happening today on the streets of New York. Woven into the fabric of the city, the NYC marathon activates our New Yorker identity, and for me, my runner identity as well. When I, along with thousands of other New Yorkers, stand on the sideline, we are not cheering for strangers. We are cheering for our people—fellow runners, fellow New Yorkers, fellow lovers of the city. For a few hours, politics, religion, and nationality dissolve. Everyone on that course becomes part of our team.

We love social rituals

Former marathon champion Paula Radcliffe famously used the same safety pins to attach her race number and Olympian Mo Farah always ran in leggings the day before a big race, even when it was 100 degrees outside. Rituals are behaviors that we perform in a specific way and that often hold special meaning to us. Runners’ rituals may give them a sense of control, helping them feel more capable of getting past the finish line.

But rituals are not just for athletes. In New York, Brooklyn’s block parties and Manhattan’s watch gatherings are just as much part of the marathon as the runners themselves. From birthday parties to family dinners, social rituals create shared experiences and give people the opportunity to bond. Meeting up with friends once a year to cheer on runners and celebrate our city is just another ritual that brings us closer together.

Cheering together connects us

When we chant the same words, clap to the same rhythm, and dance to the same song, we move in sync—literally and figuratively. Being in sync with those around us strengthens our social bonds and group identity, makes us feel more empathetic and connected, and even boosts cooperation.

In fact, research from our lab and others finds that when we are moving in synchrony, our hearts and brains start syncing up, too! One study found that when group members drum the same beats, their hearts eventually beat the same rhythm, too, and this was associated with greater group performance and feeling more connected.

Research from our lab found similar dynamics play out in the brain. When our former PhD student Diego Reinero instructed group members to tap along to the same beat, their brain waves began to align (a phenomenon called inter-brain synchrony). The more the brains synced up, the better the group performed in solving challenging tasks together.

Supporting the runners feels good

When athletes are cheered on, they often feel stronger, more capable, and even their blisters hurt less. But here’s the thing: handing out water bottles and cheering can be just as rewarding for the spectator as it is for the runner. Helping someone out and offering support is, in fact, often more beneficial to the support provider than the receiver.

In the long run, acts of service can increase people’s emotional well-being and give them a stronger sense of belonging. So if you’re in New York today, go outside and cheer. You can go back to ignoring strangers tomorrow.

This newsletter was written by Anni Sternisko with revisions and additions by Hannah Karsting and Jay.

News and Updates

We are proud to announce that a paper from our research team won the 2025 SPSP Cialdini Award, which recognizes the best field research in social psychology of the year! The project—which tested the effectiveness of 11 interventions on climate change beliefs and actions across 63 countries—was led by Dr. Madalina Vlasceanu, Dr. Kim Doell (when they were both postdocs in the lab) and Jay. But is was a genuine team effort, with 256 authors from around the world. Everyone contributed.

Our recent paper on The Psychology of Virality also made the cover of Trends In Cognitive Sciences! Here is the summary they wrote about our paper:

“Why do some ideas spread widely, while others fail to catch on? In our hyper-connected world, understanding the mechanics of ‘virality’ is crucial. In the latest issue of Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Steve Rathje and Jay J. Van Bavel reviewed the psychology of information spread. They argued that fundamental psychological processes cause similar types of content to go viral in most contexts, both online and offline, from historical gossip to modern social media posts. The paper explained the ‘paradox of virality’—where widely shared content is often not widely liked—and assessed the strengths and limitations of the popular ‘information-as-virus’ metaphor.”

On another note, we now regularly post guest lectures from our lab meetings on our Youtube Channel. We also have videos about grad school, the academic job market, and various tutorials for researchers and science communicators, so be sure to check out our channel and subscribe!

Ask Me Anything sessions for fall! Paid Subscribers can join us for our monthly live Q&A with Jay or Dom where you can ask us anything from workshopping research questions, career advice to opinions and recommendations on applying the science to the real world—for paid subscribers only.

Sept 11th: 4:00 EST with JayOct 16th 4:00 EST with DomNov 6th 4:00 EST with Jay

Dec 11th 4:00 EST with Dom

Catch up on the last one…

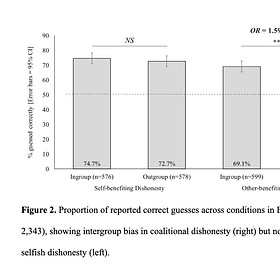

In our last issue, we summarize the results from a study that tested whether people lie more when doing so will help their in-group.

Why People Lie to Benefit Their Own Group

People will lie more if it helps a group or a team they are connected to, even with no benefits to them personally. “In short, we tend to lie more to benefit someone like us, than lie to harm someone not like us,” says Jareef Bin Martuza.