Why People Lie to Benefit Their Own Group

Issue 186: People are willing to cheat if it benefits their group — even when they gain nothing themselves (plus a recipe for psychology halloween treats!)

People will lie more if it helps a group or a team they are connected to, even with no benefits to them personally. “In short, we tend to lie more to benefit someone like us, than lie to harm someone not like us,” says Jareef Bin Martuza.

Jareef is a postdoc at the Department of Strategy and Management. Together with Jay Van Bavel from New York University and professors Helge Torbjørnsen and Hallgeir Sjåstad (Department of Strategy and Management), they have a new paper on group identities and dishonest behavior.

The researchers tested whether the tendency to behave dishonestly is influenced by the group identity of either the victim or the beneficiary of the cheating. This was studied in three experiments with more than 5,230 Americans in total, and with real money.

Is there a difference if the victim of your cheating is part of our “in-group” or is in the “out-group”?

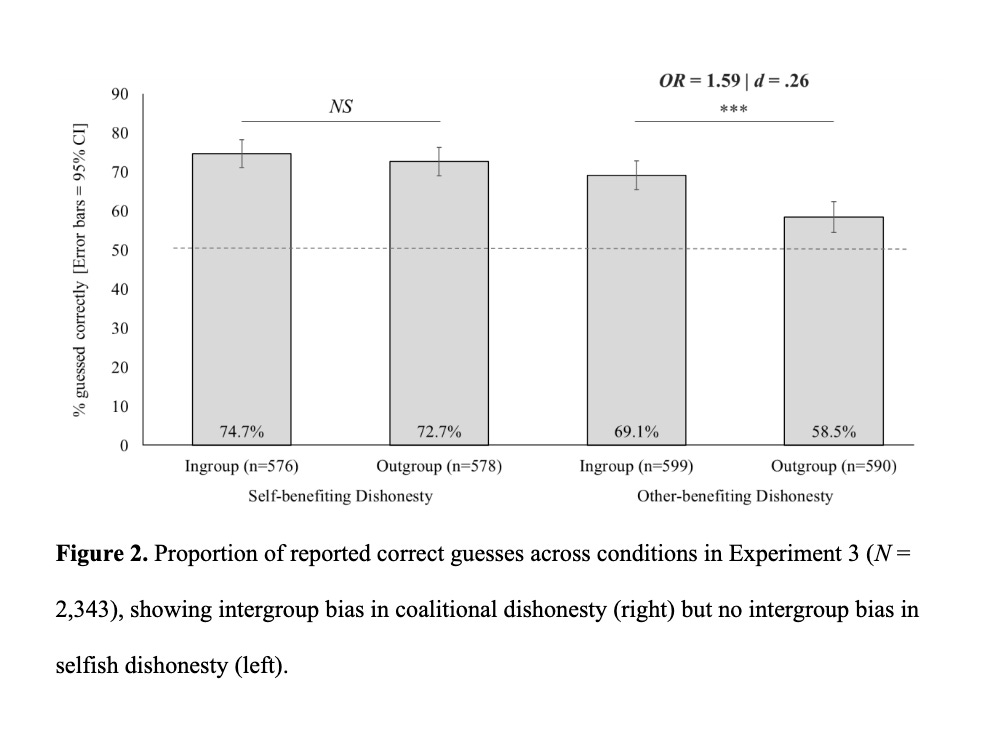

Surprisingly not. For purely selfish dishonesty, people lied equally regardless of whether it came at a cost to an in-group or out-group member.

However, when people could no longer personally benefit from cheating, a different pattern of cheating emerged. People lied significantly more to benefit their in-group than out-group members (see the figure below).

To define the “in-group” and the “out-group”, participants identifying as Democratic or Republican party voters were recruited.

In Experiment 1, participants were given the choice to tell the truth or lie, where lying would guarantee them making more money, which came at the cost of someone from their own political party (“in-group”) or the opposing party (“out-group”).

In Experiment 2, participants could lie to make more money to benefit another in-group or out-group participant, without personally gaining anything.

Experiment 3 combined both Experiments 1 and 2 and found the same results.

In all experiments, decisions were anonymous, as the experimenter, victim, or beneficiary would never know the identity of those behaving dishonestly. Neither the victim nor the beneficiary of the dishonest act knew that their fate was caused by these actions.

People also consistently overestimated out-group dishonesty more than in-group dishonesty, regardless of actual differences in behavior.

What are the implications

“The key implication is that the risk of dishonesty in organizations is not limited to selfish acts by individuals. A hidden risk may come from ‘other-benefitting’ dishonesty, where employees might bend rules to benefit their team or in-group members. For example, a team might conceal a project delay to protect the team’s reputation, or misreport facts to help a teammate secure a resource,” says Jareef Bin Martuza.

A further implication, is the problems this creates for leaders. Most people expect dishonesty to be driven by selfish motives. Standard compliance and ethics programs are often built on this assumption. As a result, they are designed to deter individual fraud but might be ill-equipped to handle unethical acts committed on behalf of a group.

“One potential solution could be to strengthen a broader, organization-wide identity. When employees’ primary loyalty is to the organization rather than their specific team, actions that harm the company for the benefit of a small group might be less likely to occur,” Jareef Bin Martuza concludes.

The paper is current under review and the preprint is available here.

The following newsletter is brought to you by an interview of Jareef Bin Martuza by Arent Kragh with edits by Jay Van Bavel

A creepy halloween treat for psychology fans

Jay made some delicious halloween treats with his kids as a tribute to Phineas Gage the most important lesion patient in the history of neuroscience. Gage famously survived an accident in which an iron rod shot through his frontal lobe. After the accident he eventually healed.

But psychologically, he was ““no longer Gage”. The accident reportedly impaired his socio-emotional capacity. This led to lots of research with people who have similar brain damage and the impact on their decision-making capabilities. You can read his full story here.

They skull cakes are a perfect treat for a psychology Halloween Party. To make your own, buy a skill shaped cake pan. Then use this delicious chocolate bundt cake recipe.

Once they pop out of the oven, cut the edges off. Then insert a pretzel into each skull using the exact parameters from this Science Magazine paper from Hannah Damasio and colleagues.

Enjoy (in moderation)!

Catch up on the last one…

Our book giveaway with Colin Fisher for his new book, The Collective Edge closes on November 4th! Check the link to navigate to this book interview and learn how you can enter for a free physical copy!