Why “doing what’s right” depends on who you are with

Issue 188: Our new paper identifies under what circumstances people act on their moral attitudes and why we are often moral hypocrites.

People strive to be “good,” praising values like honesty, generosity, and fairness. But when the moment comes to act, they often fall short. They loudly broadcast their views online but refrain from taking action in the real world. If morality is so central to our identities, why does it often fail to translate into behavior?

This framework challenges the assumption that someone’s moral behavior is a reflection of their values—this is not always the case.

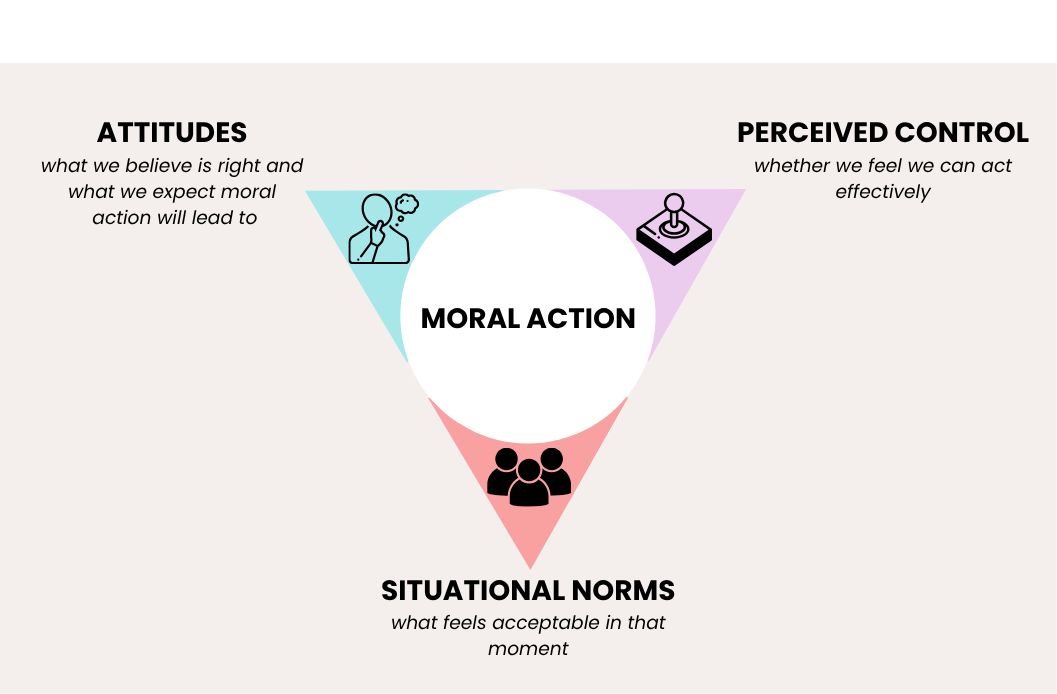

Our latest paper explains why people tune their moral behavior to fit the social context. Building on the Theory of Planned Behavior, we illustrate how moral action depends on three factors: attitudes (what we believe is right and what we expect moral action will lead to), perceived control (whether we feel we can act effectively), and situational norms (what feels acceptable in that moment). The situational norms are especially influential because they signal which behaviors will be rewarded or punished, which helps explain why the same person might speak out in one setting but stay quiet in another.

Social norms work through two goals: (1) the desire to fit in (affiliation goals) and (2) the desire to do the morally “right” thing (alignment goals). These are often described as descriptive versus injunctive norms.

Although these goals might seem at odds, they often go hand in hand. What feels morally “right” usually fits what other people are doing, so the action that seems the most moral is often what others treat as moral.

For example, people say that “following the norm” is the least compelling reason to save energy, claiming that they wouldn’t change their habits just because of what others were doing. Yet in practice, the most effective way to get people to conserve energy is simply by telling them it is the norm. Learning that others are conserving energy signals both the appropriate choice (alignment) and what most others are doing (affiliation).

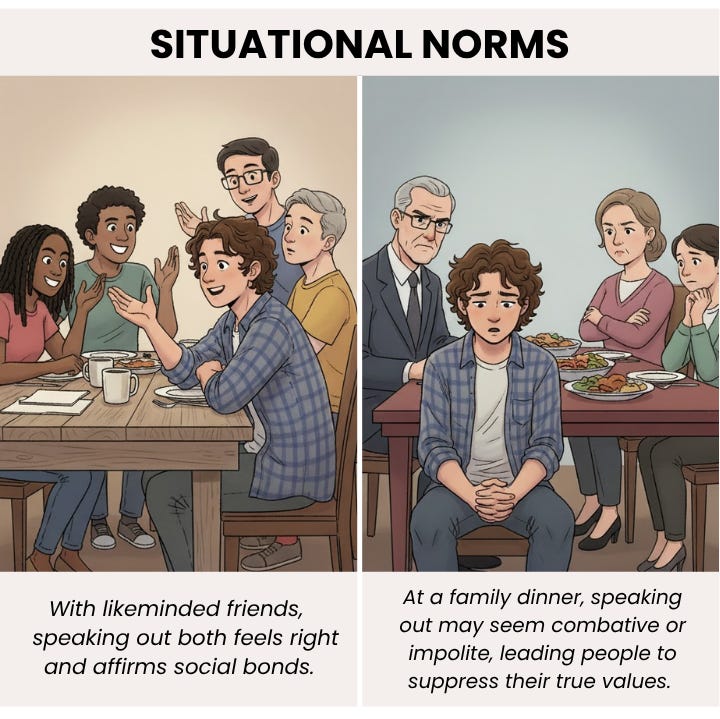

This helps explain the problem of moral hypocrisy. The same person who criticizes a corrupt politician in a conversation with friends might bite their tongue at dinner with their in-laws. Their values have not shifted, but the situational norms have, along with their audience. With likeminded friends, speaking out both feels right and affirms social bonds. At a family dinner, the same behavior might come across as combative or impolite, leading people to suppress their true values. Political conflict violates dinner-table norms and strains relationships, so the cost of speaking up outweighs the benefits.

Of course, people do sometimes act or dissent against situational norms. Moral attitudes are not just what we believe is right, but also what we expect to happen if we act. If speaking up won’t produce a meaningful conversation, why do it? Similarly, perceived control matters for moral action. You might care deeply about an issue but elect not to donate if you can’t afford it.

People are constantly weighing attitudes, situational norms, and perceived control when deciding what to do, and at times, some factors can outweigh the others. If people strongly believe they can make a difference, this can drive moral action even if the norms discourage it. People stand up to bullies if they believe they have the power to stop the bullying or others will back them. And in some cases, deeply held moral convictions can override both norms and perceived control, driving people to stand by their values regardless of the social consequences.

This framework challenges the assumption that someone’s moral behavior is a reflection of their values—this is not always the case. Rather, moral behavior is a combination of what we believe, the social costs and benefits, whether we have the resources to act, and whether we believe our actions will matter. So although people can look like moral hypocrites, they might actually be doing what feels “right” in the moment.

If we want to create environments where people act ethically, we need to highlight the right norms, make it easier to act in accordance with these values, and incentivize ethical actions. If we fail to do so, then it should come as no surprise when people act like moral hypocrites.

This newsletter was written by Kareena del Rosario and edited by Hannah and Jay. It summarizes a recent paper from our lab which you can read here!

News and Updates

Jay won the 2025 Henry & Bryna David Award from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, which honors a researcher who draws on social science to impact policy. He will be giving a lecture explaining how modern technology interacts with human psychology to create a funhouse mirror version of public opinion this week (Nov 13). You can register to attend online or in person: https://ow.ly/eejN50XntvQ

A few weeks ago, Jay and Dr. Steve Rathje were interviewed by Andrew Yang about the psychology of social media. Check out the podcast below!

Did you know you can find new studies and updates from the Center for Conflict and Cooperation on all of your favorite social media platforms? Check out our linktree and follow us on your favorite platform!

Ask Me Anything sessions for fall! Paid Subscribers can join us for our monthly live Q&A with Jay or Dom where you can ask us anything from workshopping research questions, career advice to opinions and recommendations on pop culture happenings—for paid subscribers only.

Sept 11th: 4:00 EST with Jay (this happened today and was a lot of fun!)Oct 16th 4:00 EST with DomNov 6th 4:00 EST with JayDec 11th 4:00 EST with Dom

Catch up on the last one…

In our last newsletter, we unpack what spectators cheering for strangers at NYC Marathon says about group psychology.

The Joy of Belonging: What Marathon Fans Teach Us About Human Nature

New Yorkers are famous for having no time, no patience, and definitely no interest in small talk with strangers. But today, over two million are expected to line the streets, yelling, clapping, and high-fiving sweaty people they’ve never met. It’s the NYC marathon. Some came to support their family or friends, but before long, nearly everyone in the crowd finds themselves enthusiastically cheering for strangers.

This is great for a middle school discussion!

Is the 2nd photo ai generated?