How Anyone Can Help Create Social Change

An interview & book giveaway with Michael Brownstein, Alex Madva, and Daniel Kelly about their new book, Somebody Should Do Something

The question of how to create large-scale social change is one of the biggest challenges of our time. The world seems so polarized and long-standing systemic issues require immense cooperation and agreement to even start to think up plans to make the world a better place. In their new book, Somebody Should Do Something: How Anyone can Help Create Social Change, philosophy professors Michael Brownstein, Alex Madva and Daniel Kelly tell the stories of revolutionaries around the world from the US Temperance Movement to modern-day climate activists. They analyze the effectiveness of these changemakers’ actions, discuss coalition building and explain the importance of shared social identities for building group solidarity.

“Some activists say that the antidote to despair is action. This is good advice, but adding one word would make it better: the antidote to despair is taking action together. Creating community is the building block of social change.”

In their interview below, they offer a sneak peek at some key themes in the book — one of which is a takedown of a false and harmful dichotomy: the idea that we must either make better personal choices or change the system. This “either/or” mindset between individual versus system change leaves many people feeling like their efforts are too small to matter. This can lead to paralysis and inaction. They argue that to solve large-scale problems, we need both individual action and collective effort — personal behavior and institutional reform.

Click here to learn more about Somebody Should Do Something and order a copy now! Plus, we are giving away 5 free physical copies to The Power of Us subscribers. To enter the giveaway, check out the details following the interview…

What does your book teach us about social identity or group dynamics?

Our book tells stories of changemakers, organizers, and movements around the world—from the US Temperance Movement to the “Green Tide” for gender and reproductive rights across Latin America. We make the case that success requires leaning into the power of a shared social identity. We explore a range of variations on this theme. Sometimes it means leaning into an “us vs. them” mentality, but more often it means building solidarity within a group while also expanding the sense of who “we” are.

For example, we discuss research investigating the mindsets of protestors in high-risk, repressive countries. These protestors do not tend to have an inflated sense of their personal power to make change. They don’t think they’ll make all the difference, or even expect their movement to succeed. Rather, they speak out and show up because they feel loyal to their community and the people they identify with. These individuals understand themselves as part of a “community of fate,” as Margaret Levi puts it.

We make the case that social identities are center stage in pretty much every successful endeavor to promote justice. Some social identities foment hyperpartisanship and tribalism, sure, but others don’t. They are inescapable anyway, so the real challenge is finding ways to practice identity politics well.

What is the most important idea readers will learn from your book?

None of us are solitary individuals. It’s easy to underestimate how deeply intertwined with each other we are. But because our culture is soaked in ideals of rugged individualism and self-reliance, we often forget how much we are influenced by other people, and also how much influence we can have on them.

Economist Robert Frank offers a striking illustration: the biggest danger of secondhand smoke isn’t that someone else’s cigarette might harm others’ lungs; it’s that smoking in public creates more smokers, by making it seem normal. Conversely, the number one predictor of when people quit smoking is after their spouse quits. Friends, family members, and role models exert a huge influence here, too.

Similar lessons apply to social change. College roommates have a large and lasting effect on each other’s voting behavior, and the number one predictor of when a household installs solar panels is when their neighbors do. Social influence is the air we breathe, but we exhale it, too. We are all, each of us, agents of social change.

What is one statistic or study in your book that everyone should know?

We got mad about the endless either/or debate between the “individual action” versus “systemic change” and decided to try to fix it.

Whether the topic is climate change, racism, housing policy, diabetes, gun control, or online misinformation, people get stuck thinking, “these are massively complicated, ‘systemic’ problems; aren’t the things I can do as an individual insignificant?” Our book assembles ideas and images and models and stories showing how individuals, working together, can change institutions, systems, and social structures.

In our own lives, we’ve learned to talk more about our hopes, fears, questions, and plans with others. We often don’t know what each other cares about. For example, Americans think about 1/3 of other Americans want stronger climate action from the federal government, but in reality, the number is more than 2/3rds. So, even in simply talking about climate change, we can help reshape the situations in which others make their choices.

What will readers find provocative or controversial about your book?

Some of the people we profile in the book embrace politics and tactics we expect many readers will dislike. After her daughter was killed by a drunk driver, Janice Lightner founded MADD, or Mothers Against Drunk Driving. Lightner is one of the most successful agents of change in recent American history. 25 years after starting MADD in 1980, 94% of Americans had heard of it and alcohol-related traffic deaths have decreased by 50%. MADD was instrumental here, e.g., by convincing legislators to raise the national drinking age to 21.

What struck us about this story is how MADD combined an effort to change social structures — in this case, both federal law and social norms — with a controversially punitive focus on blaming individuals, unabashedly framing drunk driving in terms of personal responsibility. In fact, the organization’s original name was “Mothers Against Drunk Drivers.”

MADD rode the 80s and 90s wave of attacking social problems through punitive criminal-justice policies, blaming individuals for broader social problems. That’s not a tactic we or (we expect) much of our readership would endorse in 2025. Emphatically, we are not saying “find someone to blame and build a coalition around demonizing them.” But the key point, for our purposes, is that Lightner was successful because she tapped into ordinary people’s attitudes and beliefs about the problem—the ambient individualism in her social environment. (An even more controversial example in the book explores the devastatingly effective identity-based tactics pursued by the NRA.)

Do you have any practical advice for people who want to apply these ideas (e.g., three tips for the real world)?

Some activists say that the antidote to despair is action. This is good advice, but adding one word would make it better: the antidote to despair is taking action together. Creating community is the building block of social change.

Doing anything is better than doing nothing. The effects of our actions, and broader social trends, are incredibly difficult to predict. This can be disheartening: maybe we toil away for long stretches without noticing any tangible results. But the unpredictability of social change cuts both ways. Big positive change could be just around the corner, and it could be that the small action you take today sets it all in motion.

Change often takes time, so take the long view. Don’t get defeated about short-term setbacks or seemingly incremental steps toward progress. Remember, for example, that many incidents of democratic backsliding in the last hundred years were followed by “u-turns,” when democratic institutions emerged even stronger than before. But those took people working steadfastly together, playing a million different roles in making change.

🎁 Book Giveaway Details 📖

To enter Michael, Alex and Daniel’s book giveaway, either…

Be a paid subscriber to the newsletter. Paid subscribers are automatically entered into all our book giveaways! We will have more book giveaways with different authors every month. You can subscribe or upgrade your subscription below.

If you are not a paid subscriber yet, make sure you have a free subscription and simply leave a comment answering one of the questions below:

What’s the most urgent structural change you think we should prioritize, and what’s one thing that everyday individual people can do to promote it?

What’s one thing you could do today to help create social change?

Note: Giveaway is open to U.S. residents only. Enter before December 30th, 12 pm PST. Five winners will be selected at random and will recieve an email from powerofusbook@gmail.com on December 31st!

News and Updates

Check out our new Ask Me Anything sessions for the Winter/Spring! Paid Subscribers can join us for our monthly live Q&A with Jay or Dom where you can ask us anything from workshopping research questions, career advice to opinions and recommendations on pop culture happenings—for paid subscribers only. Upgrade your subscription using the button below. Look out for an email from powerofusbook@gmail.com to RSVP.

January 21st @ 2:00 EST with Jay

March 4th @ 2:00 EST with Jay

May 6th @ 2:00 EST with Jay

Catch up on the last one…

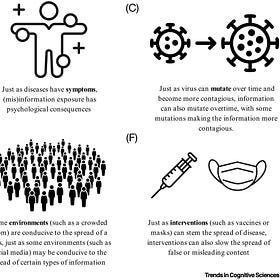

Ideas can spread like the flu. Which ones go viral and why? Decades of research and history point to the same factors.

Why Some Ideas Go Viral—and Most Don’t

Modern-day social media has profoundly changed how information spreads, with algorithms amplifying negativity, outrage, and conspiracy theories…Or has it?

Because after 30 COPs (Congress of Parties) the "trickle down" approach to solving the climate crisis has not worked AT ALL, the most urgent structural change we should prioritize is to create a volunteer-driven movement world-wide using visits and organized "Family Nights" presented by trained adults (or college students) within all existing public and private K-12 schools, rewarding families with school-aged kids everywhere for doing everything they can to become sustainable themselves within their own communities and for promoting sustainability in their neighborhoods, adding "bubble up" to the mix. This can all be financed by setting up a system that provides rebates to schools paid by local vendors of solar panels, insulation, reflective roofing, EVs, double-paned windows, and other "high ticket" energy (and water) saving services and products when families make purchases that reduce the carbon footprint of individual families and communities. When "trickle down" meets "bubble up" change will finally begin to take place.

When families understand the problem and start taking action, they will put pressure on the institutions to change. The one thing that everyday individual people can do to promote it is to start a program in their own neighborhood school like the one we are currently designing at www.greenactioneers.com that gets the entire next generation onboard the idea that we should all become "indigenous" to our own surroundings. It is only after this sort of youth and family-driven program is instituted in every country that we will "wake up" as a society and begin to attain sustainability. We will be piloting this program here in Florida in 2026 and solicit assistance to take it nationwide and eventually world-wide.

*What’s the most urgent structural change you think we should prioritize, and what’s one thing that everyday individual people can do to promote it?* This structural change is NOT isolated from others that other commenters have mentioned, but changing our healthcare policies and systems to be more equitable, fair, and ACCESSIBLE to our communities is the most important. It should be universal. Our neighbors should not be bankrupted by health issues.

*What’s one thing you could do today to help create social change?* SERVE our communities. VOLUNTEER at agencies, institutions, and groups that are making the choices affecting our communities and our neighbors.