Why Some Ideas Go Viral—and Most Don’t

What decades of research reveal about why certain content spreads—and how social forces shape what we all see.

Modern-day social media has profoundly changed how information spreads, with algorithms amplifying negativity, outrage, and conspiracy theories…Or has it?

After the invention of the printing press in the 1400s, the bestselling books were religious extremist texts and witch-hunting manuals. In other words, what went “viral” in the Middle Ages wasn’t so different from the salacious conspiracy theories you see flooding social media today.

While studies find that moral outrage and negativity about political opponents go “viral” on social media, this is also true of the offline world. Gossip is common in everyday conversation, mostly negative, and often about people we dislike.

Just as “cancellations” go viral on social media, gossip spread widely in hunter-gather societies, and was similarly centered around other people’s antisocial behavior.

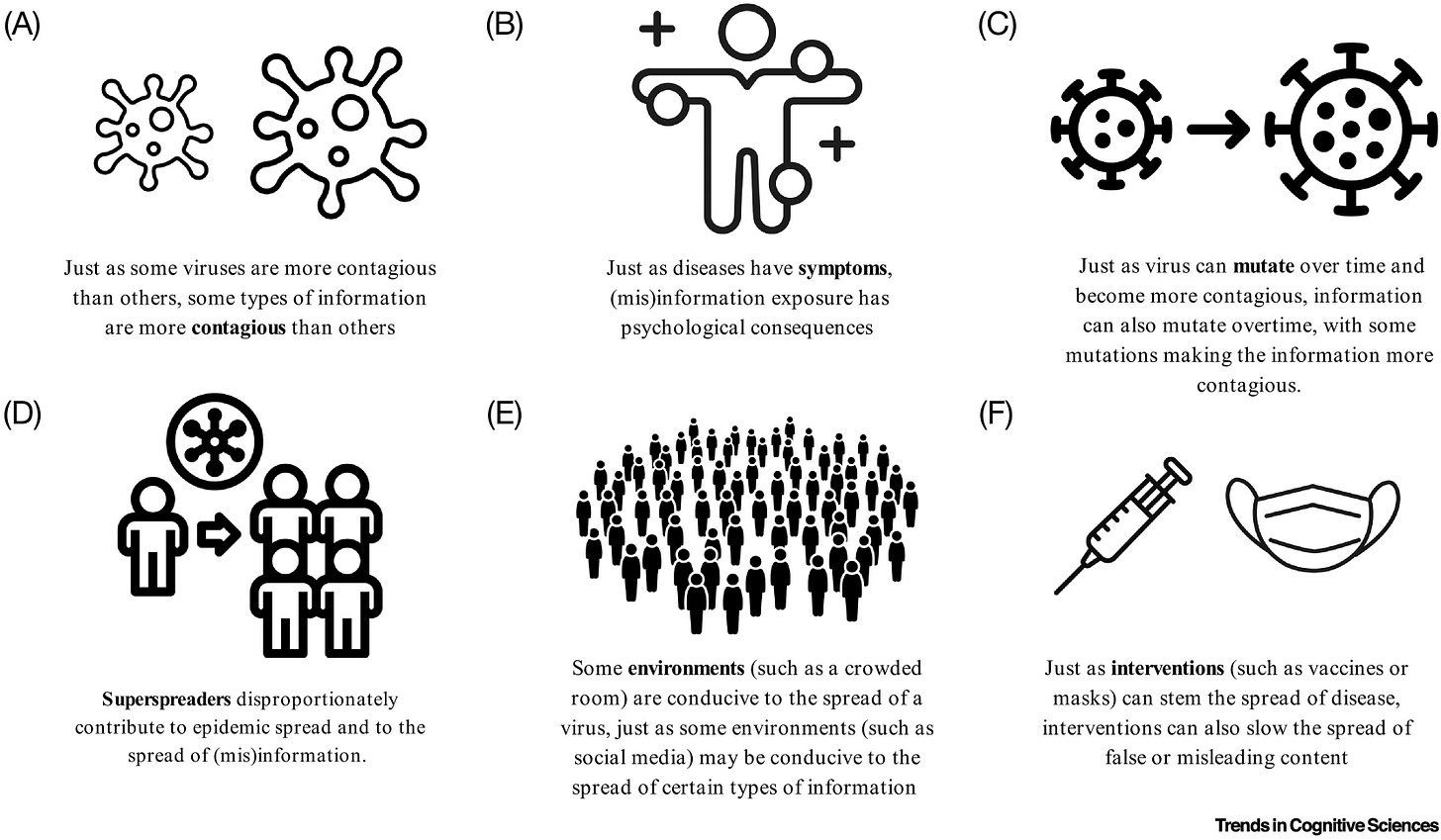

In a new paper called “The Psychology of Virality,” recently published in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, we argue that, just like some viruses are more contagious than others, certain types of information (such as negativity or outrage) are naturally more contagious than others—going “viral” in all kinds of settings.

Using virality as a metaphor is controversial, but useful, because it can scaffold on our understanding of superspreaders (eg., some people spread more information that others), interventions (eg., how to stop the spread of certain types of information), environments (eg., why some platforms facilitate the spread of information), etc. See our figure for more examples.

Certain information goes viral because it appeals to our evolved psychology. For instance, negative and intense emotions are more likely to attract our attention and be remembered, which may explain their viral spread. This “negativity bias” likely evolved because it was important to pay attention to information that could threaten our survival.

Similarly, gossip is thought to have evolved to help small-scale societies cooperate, exposing immoral actors and incentivizing people to act cooperatively to avoid becoming its target. Technology may have changed dramatically across centuries, but the underlying psychology behind the information we pay attention to and share hasn’t.

Understanding the online world requires understanding this underlying psychology. While we often assume that the anonymity of social media makes us more hostile, one series of studies reveals that this assumption is incorrect or overstated: most people who are hostile online are also hostile offline. People are surprisingly similar in their online and offline behavior. Social media may simply feel more hostile because hostile actors are more visible.

Just as a few “superspreaders” disproportionately contribute to epidemic spread, only a small handful of “superspreaders” create most of the hostile and false information online. As an example, one estimate shows that around 0.1% of fake news is shared by 80% of Twitter users. Similarly, 3% of toxic users contribute to 33% of all comments on Reddit. This can create the perception that the world is far more hostile or misinformed than it really is.

These “superspreaders” of toxic content have vastly different tastes than most people. For instance, one study found that, while most people disapprove of divisive social media from politicians, the small handful of people who frequently engage with politicians actually enjoy divisive posts. This may explain in part why our research has found that the most widely shared content online is, paradoxically, not widely liked.

But there is a key difference between the online and offline world: while gossiping a little bit predicts more friendships, those who gossip the most offline have fewer friends. By contrast, extremists who frequently share divisive content online tend to have the most followers and highest engagement—in part because of recommendation algorithms designed to promote the most attention-grabbing content.

Outrage may have always gone viral. But just as viruses spread faster in a crowded room, social media is a context that allows superspreaders to spread hostile content faster and farther than they ever could have before.

So, what is the solution?

Not letting “virality” rule our lives. Our research has found that the vast majority of people across the political spectrum say that they want social media algorithms to promote positive, educational, and nuanced content. Yet these platforms promote toxic content that nonetheless grabs our attention. We can change social media algorithms so that they amplify what we want to see, rather than what we can’t look away from.

Just like we can slow the spread of viruses (through masks, distancing, vaccinations), we can also slow the spread of viral information. Doing so can have positive consequences: for example, WhatsApp found that putting limits on how much a message could be forwarded helped curb the spread of viral misinformation.

We live in a world where the main way we organize and filter our online information is via algorithms that show us the most viral posts. But, we know, from psychology and history, that the most viral content is often the most harmful. The printing press made information spread faster, but after this, people needed to develop institutions to help organize, filter, and make sense of the flood of information. Using “virality” as the main way to decide the information people see every day will (like actual viruses) make us sick.

News and Updates

Check out our last Ask Me Anything session for the fall! Paid Subscribers can join us for our monthly live Q&A with Jay or Dom where you can ask us anything from workshopping research questions, career advice to opinions and recommendations on pop culture happenings—for paid subscribers only. Upgrade your subscription using the button below. We will be posting more sessions in the new year.

January 21st @ 2:00 EST with Jay

March 4th @ 2:00 EST with Jay

May 6th @ 2:00 EST with Jay

Catch up on the last one…

Check out where you score in intellectual humility in our scale posted last week. It turns out that intellectual humility is a great trait to have. People who score high on these measures are less likely to spread conspiracy theories or misinformation, express out-group prejudice, and feel polarized.

This helps separate what feels new from what’s actually enduring. The throughline from gossip and outrage in small societies to algorithmic amplification online makes it clear that technology accelerates tendencies that were already there, rather than inventing them.