Why video evidence is unable to create a shared reality

Why partisans disagree over the tragic shooting by an ICE agent

In the aftermath of the tragic shooting of Renee Good by an ICE agent in Minneapolis, the public quickly turned to video footage in search of clarity. But as people watched the same painful video, they came to vastly different conclusions. (This clip from the New York Times website shows the event from multiple angles).

In an interview with the press, President Trump asked his aide to pull up the video. Surely, if we could just see what happened, disagreement would fade. It did not.

Despite watching the exact same video, people reached radically different conclusions.

How can that be?

The myth of the objective camera

Many of us place enormous trust in video evidence. When anything newsworthy happens, people immediately pull out their cameras to document the event. Indeed, this single event was videotaped by numerous bystanders, along with the ICE agent who shot Goode. And in his video, you can see Goode’s wife, Rebecca, taping him in return. Everyone was recording everyone in the video.

With multiple angles of real time video footage and the camera as our neutral witness, we expect people to see events objectively. Surely this is an opportunity to build a shared sense of reality. We assume that justice should follow naturally.

And yet, in an age when nearly every encounter can be recorded in high definition, video evidence often fails to settle our disputes or strip legal decisions of biases. In fact, it sometimes does the opposite.

Why? Because our eyes don’t work like cameras.

An eye captures only about 1-2 degrees of our visual field in high resolution. The rest is blurry. Our eyes are also constantly jumping around, and during these rapid movements (“saccades”), visual input briefly shuts down.

What we confidently have “seen with our own eyes” is not a perfect replica of the world. It is an image that our brain has stitched together from the few bits and pieces that our eyes were able to gather.

And what visual information we gather and how we stitch it together is deeply shaped by who we are.

When we look and still don’t see

Attention is guided by our social identities. We attend differently to people who belong to “us” and those who don’t. For instance, outgroup members tend to capture our attention quicker, but our eyes often linger longer on ingroup members. These patterns can unfold in milliseconds, long before our conscious thought enters the equation.

Missing key moments is therefore not always willful blindness. In a classic study on “inattentional blindness”, many participants didn’t notice a person in a gorilla suit walking through the middle of a scene because they were focused on counting basketball tosses. You can show the video (below) to a few friends to measure the accuracy of their attention.

Social identity can shape this blindness: White participants were less likely to notice a Black man than a White man interloping a scene. Group based attentional biases are especially pronounced when people are under perceptual load. Even the most obvious events can fail to register when our minds are somewhere else.

From biased views to biased judgment

Biased attention often means biased judgment.

Decades of research on the weapon (or “shooter”) bias finds that, under time pressure, people are more likely to mistake harmless objects for weapons when they are held by outgroup members, partly because attention is allocated differently. For example, participants are quicker to shoot armed outgroup targets than armed ingroup targets in a mock shooting task. These biases often operate automatically, and researchers have observed them even among trained police officers (though typically attenuated).

In a study led by Yael Granot, we tracked eye movements as participants watched an altercation between a police officer and a civilian. Social identity shaped where viewers looked, and those who focused relatively more on the officer later assigned greater responsibility and harsher punishment.

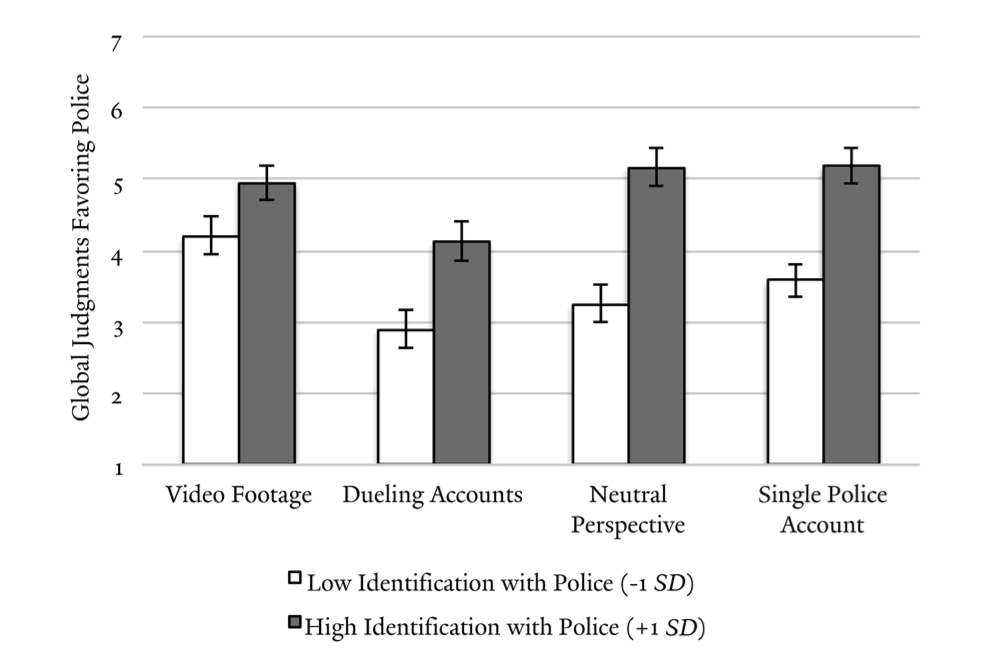

A similar paper in The Yale Law Journal found that prior attitudes toward police significantly affected participants’ judgments of the officer’s conduct—regardless of whether they saw video evidence or learned in other ways—and the degree of bias did not differ significantly across the different types of evidence (see figure below). Furthermore, people who identified strongly with the police—but not those who identified weakly—became more confident in their judgments when presented with video evidence.

This means that disagreement over video evidence is not always about dishonesty or bad faith. Sometimes, people are simply not watching the same scene. Moreover, it suggests that video evidence can even increase polarization among people who highly identify with the policy compared to those who don’t!

When video evidence challenges what we want to see

When video evidence contradicts what we want to believe about “people like us” or the institutions we trust, our perception can shift to protect those beliefs, and this can happen outside of our awareness.

This dynamic may have played a role in the trial following the killing of Jonathan Ferrell. Jurors reviewed the same video evidence yet saw different events unfold. While a White juror saw “a very aggressive move towards these police officers”, a Black juror saw the opposite. The jury ultimately deadlocked, divided largely along racial lines.

Similar patterns can appear outside the courtroom. In one study, partisanship influenced how participants saw and interpreted footage from the Women’s march. Supporters of President Trump viewed the protest as more extreme and later recalled more violent and fewer peaceful actions than had occurred.

Sometimes, we are seeing the world through group-colored glasses.

Changing our viewpoint

When we watch video evidence, many of us cannot step outside our social identities. But we can change how we engage with it.

Research suggests that when viewers are prompted to watch all parties equally or when the footage they watch includes multiple perspectives, their judgments can become more balanced. This is why we encourage you to watch all angles of the footage before forming an opinion—and you probably shouldn’t trust the opinions of hyperpartisans. Watch all the videos for yourself and draw your own conclusions.

Justice isn’t just about what evidence we have, but how we watch it. It is also about the institutions and processes designed to reduce harm and ensure accountability. Core priorities of law enforcement are no loss of life, de-escalation, and an impartial judicial process. Reducing tension and avoiding escalation requires attention, training, and institutional support.

It also requires effective public leadership. Leadership that prioritizes de-escalation and emphasizes thorough investigation matters at all times, and becomes especially important during periods of polarization. Understanding the limits of human psychology reminds us why impartial institutions and an independent justice system are crucial.

If you want to delve deeper into the psychology of visual attention and the justice system, check out the book chapter that Anni co-wrote with Yael Granot and Emily Balcetis.

This newsletter was written by Anni Sternisko and edited by Jay Van Bavel. ChatGPT was used to improve grammar and clarity.

Interestingly I too wrote a piece on Reality yesterday.

If you may find it useful, here it is - https://open.substack.com/pub/tarunagarwala/p/what-is-reality-really-and-what-does?r=9ggqf&utm_medium=ios&shareImageVariant=overlay

A mental conflict occurs when beliefs are contradicted by new information. This conflict activates areas of the brain involved in personal identity and emotional response to threats. The brain's alarms go off when a person feels threatened on a deeply personal and emotional level, causing htem to shut down and disregard any rational evidence that contradicts what they previously regarded as "truth".

Meanwhile...

The media - both news and entertainment - have now politicized nearly everything in our society as an extremely powerful mechanism of control.

Politicization is so effective at manipulating the populace because most people emotionally connect their personal belief system to the belief system of their political party, and so then any attack on their party - legitimate or otherwise - is interpreted by their brain as an attack on themselves. Reason and logic then jump out the nearest window as raw emotion takes the helm, thus making them even more susceptible to the predatory controlling influences.

Our thought process can often be boiled down into terms (often ultimatums) of – this or that – and our adversaries understand - very well - the art of this war.

Excerpt from and much more on these fatal cognitive exploits here: https://tritorch.substack.com/p/there-is-something-way-bigger-going