Policing, Protests, and Us: Why Force Deepens Division

An identity-based account of how crackdowns on demonstrations can intensify collective action — in the wake of the Minneapolis ICE killing.

A time-lapse of New York Times headlines from the past week reveals a dramatic escalation of violent conflict between ICE and protestors in Minnesota:

Jan 8 — Woman Is Killed By Federal Agent: Local Officials Urge ICE To Leave Minnesota

Jan 9 — Dispute Heats Up On Investigation Of ICE Shooting: More Agents On Way

Jan 10 — Local Officials Demand Role In ICE Inquiry: Minnesota Is Wary Of Federal Conclusions

Jan 13 — FBI Searches For Activist Ties In ICE Shooting

Jan 14 — ‘Like A Military Operation’: Clashes Rise With Federal Agents In Minneapolis

Jan 15 — Local Outrage Propels Cities To Resist ICE

Jan 16 — Trump Sharpens Threat As Clashes With Agents Continue In Minnesota: Says Insurrection Act Could Be Invoked

As group dynamics researchers, we are sometimes accused of seeing identity everywhere and in everything. Fair enough. But when it comes to ongoing protests – whether those in Minneapolis (and spreading nationally) in response to the shooting of Renee Good by an ICE agent or in Iran driven largely by economic dissatisfaction with the regime – social identity is truly relevant around the world right now.

The same basic questions keep resurfacing: who gets to define “us”, who is pushed into “them”, and what happens when those definitions collide?

Focusing on the growing protests in the United States against ICE, we see identity dynamics playing out in three interlocking ways.

1 - Arguments Over the Identity of the Victim

The first move in many tragic, contentious, and tragically contentious episodes like the shooting of Renee Good is a fight over the victim’s identity, over whether the person at the center of the story counts as “one of us” and is therefore worthy of our moral concern.

That is why immediate attempts by ICE and the Trump administration to categorize Renee Good as an activist, a professional agitator, even a deranged lunatic, are not incidental but strategic. If the victim can be recast as an atypical citizen, then this event does not represent the killing of an ordinary American—and thus to ordinary citizens does not reflect something that could happen “to someone like me” or signals the victim is undeserving of their empathy.

This is one of the most basic identity moves in the playbook: narrowing the definition of the harmed ingroup so that the harm does not generalize to others.

2 - Identity Fault Lines

A second fault line has emerged between local and federal authorities. Following the shooting, Minneapolis leaders demanded that ICE leave immediately, framing the federal presence as “chaos” that makes the community less safe. Minnesota’s Bureau of Criminal Apprehension described being cut off from evidence and withdrew from the investigation, arguing it could not meet the investigative standard Minnesotans expect without full access. The Hennepin County Attorney’s Office created an evidence portal and publicly solicited information to preserve materials while state officials were blocked from the federal investigation.

Meanwhile, the feds deployed 2,000 additional agents to the Twin Cities and President Trump threatened to invoke the Insurrection Act, which would allow him to send in military troops.

This is not just a dispute about jurisdiction, it’s a dispute about “who we are” and “who governs us”. Minneapolis was also the site of the police killing of George Floyd in 2020, and in the protests following that event, the community and local law enforcement were markedly not part of the same coalition. Yet, at least for now, there appears to be a degree of common cause between the citizens protesting in the frigid winter streets and the local cops, with both arrayed against an external force (this interview with Minneapolis mayor Jacob Frey is worth a listen in this regard).

These tensions may not yet have fully hardened into a local community vs. occupying force dichotomy, but they are headed in that direction. To the degree that this happens, we predict that cooperation by either side will start to look like capitulation and skepticism like defiance.

3 - An Escalation Loop

The third identity dynamic is counter-intuitive to many: protests often grow less because of outrage triggered by an initial spark (Renee Good’s death, in this case), but because of the police response to the protests.

Aggressive protest enforcement doesn’t just manage a crowd, it can actively reorganize how people categorize themselves. In this case, as Minnesota residents experience a heavy federal presence, including masked agents, tear gas, arrests, and detentions, the situation for an ordinary citizen can quickly shift from “I’m an observer” to “I’m on the side of the protestors” to “I’d better get out there myself to defend my community".

This man-on-the-street interview recorded within the past few days captures how this social psychological dynamic unfolds:

Interviewer: Have you ever gone out to these sorts of things before?

Protestor: Never. Never. I’ve never protested in my life… I’m far enough away, but close enough, and I sit in my cushy house and look at shit and get mad… They’re just trying to fucking scare people and, you know, but but but why shoot people? You know what really pisses me off is the fact they detain people, cuff them, and then still beat the shit out of them. They tell you it’s only immigrants. It’s fucking anybody…

Interviewer: Sounds like you don’t fit the definition of the ah…

Protestor: I’m not fucking paid to be here like everybody fucking says… I gotta work in the goddamn morning just like everyone else. I’m just here trying to stand up for my community, dude. We’re all human beings here…

This person is by no means a longtime activist or an ideologue. He embodies movement across categories: from a mere observer in his living room to a morally-outraged community member to a full blown protester, taking to the streets.

Sweeping labels from federal authorities, who call protestors “agitators”, “insurrectionists”, or “domestic terrorists”, deepen the divisions and heighten the tensions. They can create an increasingly hostile crown by pushing an otherwise diverse set of people, folks there for different reasons, into a shared “us” opposed to a threatening “them”.

The irony is that treating a crowd as a uniform group of troublemakers can have the effect of making troublemaking normative. Aggressive policing, in other words, tends to produce aggressive protesting, rather than reduce it.

Making Sense of Protests

The Elaborated Social Identity Model of Crowd Behavior describes the identity dynamics that underlie the response to aggressive policing. Crowds that are initially loosely connected become unified when people who aren’t identified as protestors are made to feel like protestors because they are treated like them—gassed like protesters, arrested like protestors, talked about like protestors, etc. As that happens, their identities shift and a new social identity can emerge with new norms about what is justifiable, what is necessary, and what “one of us” should do.

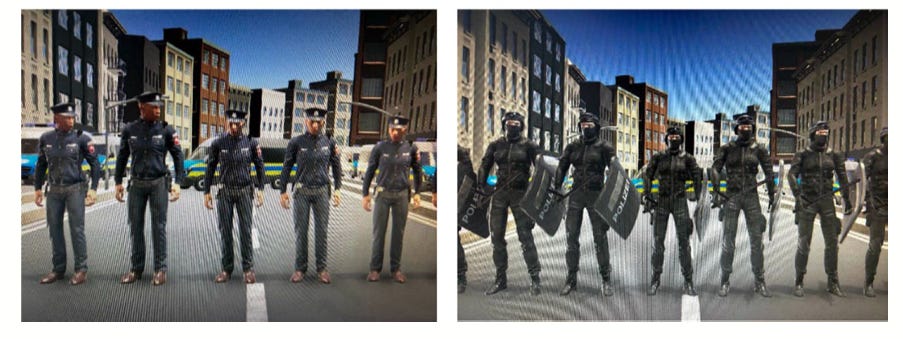

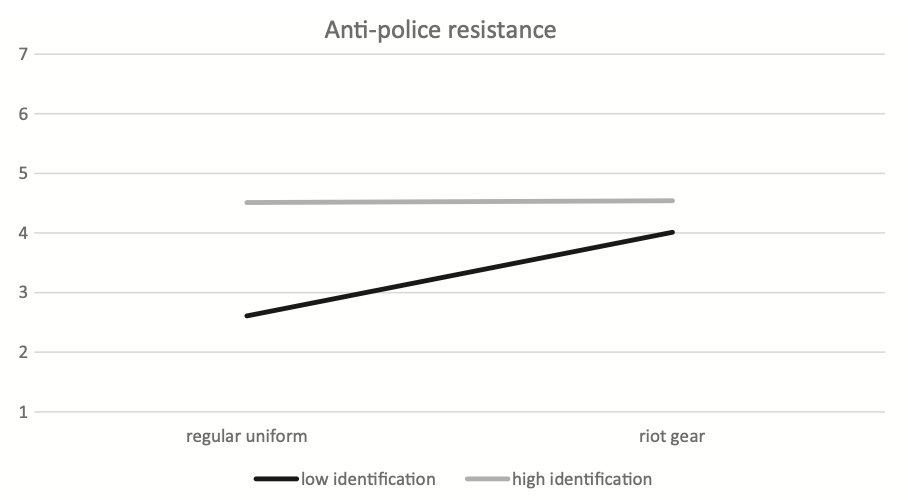

A recent virtual reality experiment conducted by Julia Becker and colleagues demonstrates these dynamics in action. People who were part of a VR protest were stopped by police either dressed in their regular uniforms or decked out in riot gear (on the right in the image below).

The police in riot gear were perceived as less legitimate than those in their regular uniforms and increased peoples’ intentions to resist the police. Importantly, these effects were strongest among individuals who were less identified with the protest movement to begin with. Like the guy on the street in the interview above, aggressive policing triggered a reaction among those with the least initial involvement.

Another factor is that aggressive policing disrupts non-violent norms among protests. Normally, protests will proceed peaceful and extremists within the community will often be sanctioned socially by fellow protestors. They might be seen as ‘too radical’ or unlikely to help the cause. But once aggressive policing takes place, the radical elements in the crowd are more likely to receive support. This can lead to everything from property damage to violence against authorities.

Thus, police have a vested interest in de-escalating the situation. Indeed, this is why most police recruits are intentionally trained to minimize the conflict in these situations and keep themselves out of harms way. When things escalate, it puts everyone at risk.

The Escalation Loop