Why do people cling to false beliefs?

Issue 51: Introducing our four-part video series on the psychology of groups and social identity. This week we focus on cult psychology and how people respond when their beliefs are falsified.

We are excited to introduce a new four-part video series where we dive into key concepts from The Power of Us. With support from the Templeton World Charity Foundation, we produced videos that combine both animation and interview style formats to illustrate and summarize key concepts from the Power of Us book. This week, we feature content from Chapter 4 and dive into the question:

“Why do people cling to false beliefs?”

Humans go through incredible lengths to preserve their identities. From cults to politics, people often defend their group’s beliefs in the face of clear contradiction.

One of our favorite examples was the Seekers cult, which was active in Chicago in 1954. Dorothy Martin, who seemingly was an ordinary resident, was the cult’s leader who claimed she could communicate with aliens from the planet Clarion. Through her communications with them, she learned that a flood was going to annihilate the U.S. West Coast.

However, a visitor from outer space would visit at midnight on December 21st, 1954 to escort her and other faithful believers to a waiting spacecraft to escape the flood.

Dorothy spread the news, which attracted new believers. Bound together in their stronghold, the Seekers gathered and waited patiently as the clock ticked towards midnight on the night the aliens were supposed to arrive.

But as the clock struck 12:00am, nothing happened.

Someone pointed to another clock that read 11:55pm.

“It must not yet be midnight!”, they thought.

As the Seekers shifted their attention to this new clock, it continued to tick. And no aliens arrived.

The group sat in stunned silence for hours well into the middle of the night. They faced the terrifying prospect that their entire belief system was wrong. This was a moment of considerable cognitive dissonance: should they leave their cherished group or could they find a way to rationalize this failed prophecy?

Then something astonishing happened. At 4:45am Dorothy conveyed a new alien message:

“Actually, our hopes were so strong tonight, that God saved the world for us!”

Rejoicing, the Seekers cheered, believing that they had, through their faith, spared the future of humanity.

In the back of the room, unknown to the Seekers, was Leon Festinger — a social psychologist who was observing the group’s response to this most peculiar evening. Leon Festinger later wrote about the Seekers in the book, When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group That Predicted the Destruction of the World.

Festinger identified several factors that led people to cling to their false beliefs. Two of the biggest factors were their initial commitment to the idea (true believers) and another was receiving social support from others to continue believing. It might be easy for most of us to let go of a belief when it is contracted by reality, but having a community of people we care about to reassure us that the belief is still true makes it much harder to move on.

The story of the Seekers is an extreme example of group members holding on to false beliefs, but there are also more recent examples in our daily life. For instance, people may fall into online or real world communities with very strong belief systems. This often happens on social media, where we tend to interact with like-minded people who often reinforce our patterns of thinking.

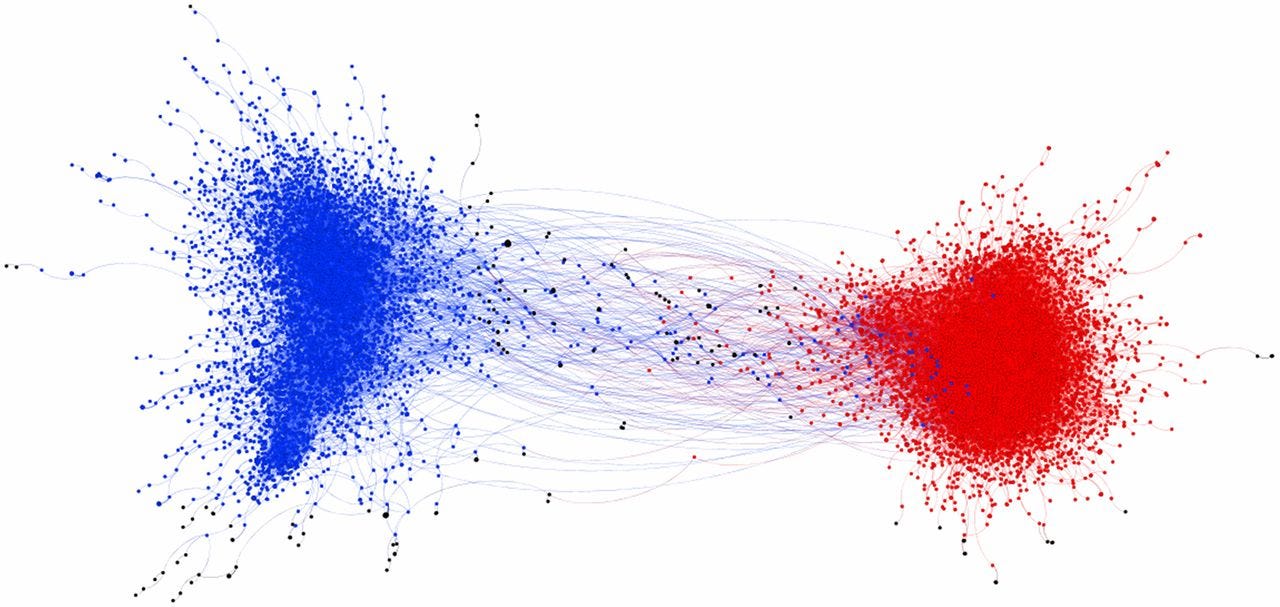

This effect is emphasized by the use of moral-emotional language. In an analysis of tweets by ordinary citizens, Billy Brady and colleagues found that when people used moral emotional language, it was associated with disconnected echo chambers. Specifically, liberals tended to retweet messages from other liberals and conservatives from other conservatives. While messages with moral emotions spread like wildfire within these groups, they rarely seemed to appeal to people across the political divide.

This image shows messages containing moral and emotional language, and their retweet activity, across several political topics (gun control, same-sex marriage, climate change). The two large communities were shaded based on the ideology of each community (blue represents liberals, red represents conservatives). From Brady et al., 2017.

Thus, our research and the story of the Seekers leaves us with three key lessons on escaping echo chambers and understanding why people may cling to false beliefs:

Be aware of how moral-emotional language is used on social media (or elsewhere)

Be aware of our own language on social media (and how it affects others)

Be aware of how groups, from cults to organizations, can act like echo chambers

Click here to watch the first video, “Why do people cling to false beliefs?”, and let us know what you learned or what stood out to you!

News and Updates

The Power of Us was chosen as the winner of the American Psychological Association’s William James book award! Jay and Dominic will present a symposium about The Power of Us at the 2023 conference in Washington, DC, August 3-5, 2023.

Jay spoke on a panel with Charles Duhigg and Annie Murphy Paul at the Aspen Ideas Festival! The panel was on how we can create more connected communities. You don’t need a ticket to the festival to see it, the video is available on-demand at this link or in the post below.

Catch up on the last one…

And in case you missed our previous newsletter, featuring a story from Jay’s elementary school days AND psychology research, you can read it here.

This week’s newsletter was drafted by Yvonne Phan, the Power of Us’ science communicator.