Why are we suckers for Astrology, the Myers-Briggs, and other pseudoscientific personality tests?

Astrology signs and MBTI do not predict people's lives (but the Big 5 does). We explain why people love them nevertheless.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is the most popular and well-known measure of personality. It is also big business. It’s a favorite among the LinkedIn Crowd, Fortune 100 companies, and government agencies. 50 million people have taken the assessment and it is used by 89% of Fortune 500 companies to screen and evaluate employees. This mini-industry generates over $20 million in annual revenue for the Meyers-Briggs Company.

The test is also being used to determine our love life. Yes, people actually do put their Myers-Briggs category on their Tinder profiles and funders gave 1 million dollars to develop an app that matches couples based on their Myers-Briggs personality types. The test also makes a pretty regular appearance on dating profiles and NYT Wedding announcements, like a charming young couple below who decided to evaluate their romantic capability:

Things were going so well that Ms. Maillian suggested they take the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, a personality test, on their phones.

“Out of 16 different personality profiles, both of us were ESTJ-A,” said Ms. Maillian. “I couldn’t believe we are both the executive mind-set. That reinforced a compatibility.”

While the Myers-Briggs test is telling people who to hire and marry, scientists hate it. As Laith Al-Shawaf notes, “any psychologist will tell you, it’s mostly bullshit.”

Then why is it so popular?

We explain why people are suckers for terrible psychology tests—from the Meyers-Briggs to the Zodiac—and how you can assess your personality with a scientific valid measure. We also share our own personality test scores, for the curious.

But let’s start with the MBTI. The test was develop during World War II by an American mother and daughter who were fascinated by Carl Jung’s 1921 book “Psychological Types”. They created a series of 93 forced-choice questions, like the following: “Are you more (a) realistic than speculative or b) speculative than realistic.

Based on these answers, the MBTI categorizes people into a group based on four personality dimensions (the sample question above is used to determine if you are sensing or intuitive):

Extraversion (E) or introversion (I), which measures whether you get energy from outwardly focused action like socializing or from inwardly focused activities like quiet reflection

Intuition (N) or sensing (S), which measures how much you see big picture patterns rather than focusing on sensory information from direct experience

Thinking (T) or feeling (F), which measures whether you make decisions using logic rather than by focusing on feelings

Judging (J) or perceiving (P), which measures your preference for structure rather than spontaneity

After you complete the Myers-Briggs test, you get sorted into one of 16 categories. Each group is often given an appealing name: the “logical pragmatist”, “compassionate facilitator”, or “insightful visionary” — providing a perfect new title for a professional development seminar or your online dating profile.

Another perk is that you get matched with famous people (most of whom are long since deceased and never completed the test). Are you an “ISFP” like Bob Dylan and Rihanna or an “INTP” like Albert Einstein and Tina Fey?

We (Dom and Jay) both completed the test and were categorized as “Commanders” with an ENTJ personality type. This puts in in prestigious—and tyrannical—company, like Steve Jobs, Margaret Thatcher, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Gordon Ramsay. Our editor, Yvonne, fared a bit better and was categorized as an INFP, like John Lennon and Princess Diana. Here is the MBTI test if you want to try it yourself. And remember that none of these historical figures probably ever completed the MBTI.

Despite the joy of being compared to celebrities, psychologists have repeatedly argued that the Myers-Briggs has dubious predictive ability and is grounded in debunked theory. To make matters worse, it’s unreliable. Which means that if you take the test more than once to learn more about your “true self”, it’s quite likely to give you different answers each time.

Another big problem is that these 16 categories contradict how contemporary psychologists think about personality. Most experts agree that human personality can be boiled down to five traits—the BIG 5: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness to experience, and neuroticism. Each trait is a continuous dimension, so that someone can score high, low, or anywhere in between. To take the same Big 5 test for yourself, follow this link to take the 120-item measure.

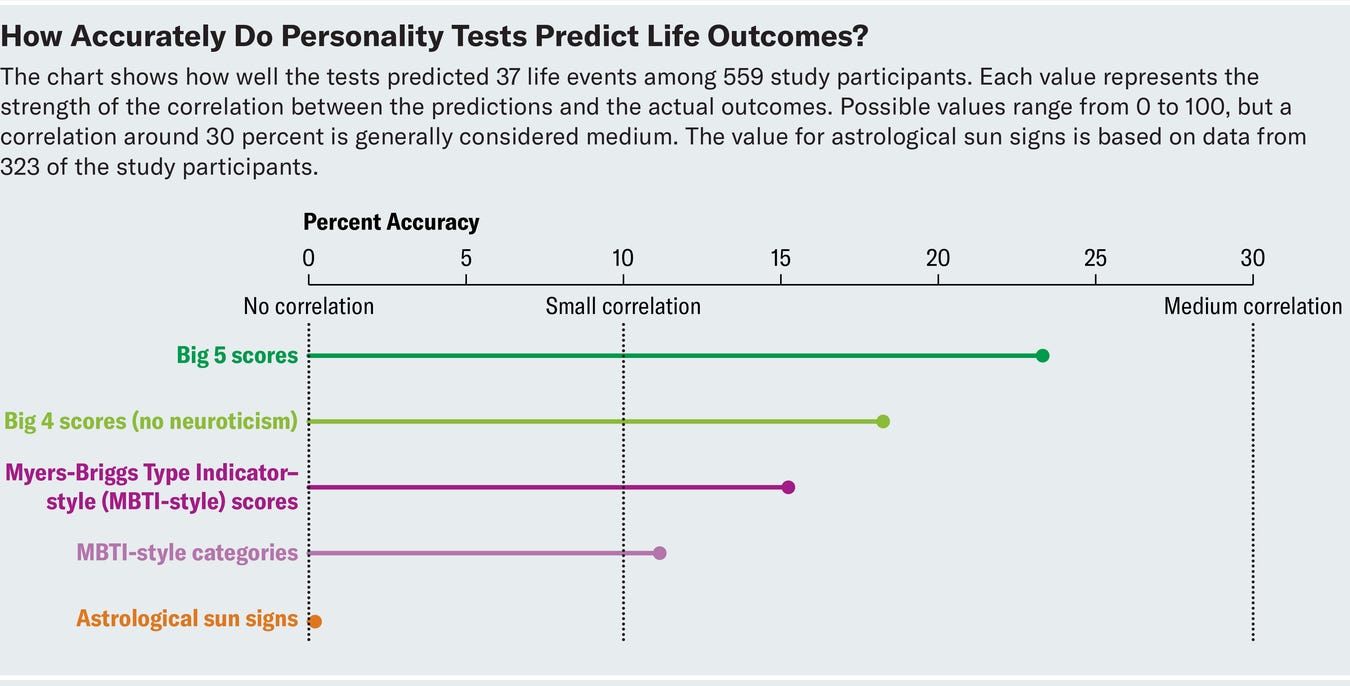

A recent report in Scientific American compared the Meyers-Briggs to other personality scores, ranging from the Big 5 to Astrological signs (see their results in the figure below) to see how each predicted 37 life outcomes (see their full report for details), ranging from how many close friends they had to how often they exercised to how satisfied they were with life.

Here is what they found:

On average, the Big Five test was about twice as accurate as the MBTI-style test for predicting these life outcomes, placing the usefulness of the MBTI-style test halfway between science and astrology—literally. When we tried predicting these same life outcomes using astrological sun signs (e.g., whether someone is a Pisces or Aries), we achieved zero prediction accuracy. In other words, sun sign astrology didn’t appear to work at all for predicting people’s lives. And while the MBTI-style test fared better, it was still often wrong in its predictions. What’s more, adding MBTI-style personality results to Big Five ones didn’t lead to predictions that were any more on the mark than Big Five ones alone.

What is it about this scientific mess that people so readily buy into? We believe that one of the bugs that drives psychologists crazy is actually a feature that explains the test’s enduring popularity.

Unfortunately, however, it is quite hard to conceive of yourself in five-dimensional space. It’s also awkward to tell people at a conference, first date, or a job interview that you have a moderate score on extraversion, moderate-to-high on agreeableness and conscientiousness, high on openness, and moderate-to-low on neuroticism. This is hardly sparkling dinner party conversation!

This is why assigning people to Myers-Briggs’ categories is compelling. Scoring low on extraversion and high on openness doesn’t sound particularly impressive, but being a “mastermind” does. People would much rather claim a social identity that includes Sun Tzu, Isaac Newton, Jane Austen and Arthur Ashe (setting aside the absurd fact that several were deceased hundreds of years before the test was even invented).

The use of categories is a great marketing maneuver and a big part of the reason behind the popularity of many dubious personality tests from the Myers-Briggs to the infamous TIME Harry Potter Quiz or Cosmo’s quiz to help you learn what kind of lover you are. The same logic also applies to Astrology signs!

All these tests operate a bit like the Sorting Hat from Harry Potter, slotting us into different groups. People crave self-definition and social identities provide this for us. We are attracted to group memberships that provide both a sense of connection to people just like us and distinction from others—what Marilynn Brewer termed “Optimal Distinctiveness”. These groups fulfill multiple core social needs.

The ease with which people form group identities can be traced back to one of the most important studies in social psychology (we personally think it is the most important experiment in our field). In the minimal group experiments from the 1970s, people were randomly assigned to groups after completing a test of dubious merit, such as their ability to estimate the number of dots in an image or their preference for abstract art (e.g., Klee vs. Kandinsky).

Within minutes, they had created a new sense of identity and were treating their new in-group members very differently from out-group members. In fact, this research revealed that the mere act of being categorized as a member of a group was sufficient to cause discrimination. It also inspired on the of the most important theories in the social sciences—Social Identity Theory.

When we use personality tests that impose categories—like the Meyers Briggs or Astrology—we risk exaggerating the differences between groups and the similarities within them. When this occurs with other types of identities like race or gender, we typically call it “stereotyping” and we try to avoid it. When consultants do it in companies, they are exploiting the same social psychology and doing it on dubious scientific grounds to make a buck.

There is reason for caution when it comes to categorizing others too readily by personality as well. We might well fail to hire, promote, or even marry someone because they fall into a false category about which we make exaggerated assumptions. Even with the Meyers-Briggs, putting people into categories is the weakest use of the test. It is roughly as useful as astrology.

This is why organizations could do much better by creating other meaningful social identities. If you can create a sense of belonging around other social identities, people might feel less of a need to rely on these dubious tests to create a sense of self.

It is also why you should focus less on fictitious identities—like whether you are a Commander or an Aries—and more on real ones that matter. And if you do want to make romantic decisions based on personality, we highly recommend using a scientifically valid personality test like the Big 5.

For both men and women, their partner's conscientiousness predicts their own future job satisfaction, income, and likelihood of promotion, even after accounting for their own conscientiousness. There reason is because conscientious partners (both men and women) perform more household tasks, exhibit more pragmatic behaviors that their spouses are likely to emulate, and promote a more satisfying home life, enabling their spouses to focus more on work.

Choosing a partner is one of the most important decisions you’ll ever make. And relying on the Meyers-Briggs or the Zodiac is about the worst way you could make that decision.

Learn more about THE POWER OF US

If you like our newsletter, we encourage you to check out our award-winning book “The Power of Us: Harnessing Our Shared Identities to Improve Performance, Increase Cooperation, and Promote Social Harmony”. You can learn more about the book or order it from the links on our website (here or scan the QR code below). We keep the newsletter free, but are extremely grateful if you have a chance to purchase the book or buy it for a friend who wants to learn more about group psychology.

Catch up on the last one…

Happy 2026 Winter Olympics! We share profound examples of cross-cultural collaboration in last week’s post. With interesting anecdotes about displays of national identity and olympic village hook-ups.

Bottom line, most people prefer bullshit over uncomfortable or hard to discern truth.

I think it’s a mistake to conflate usefulness with predictive validity here, outside the narrow critique of corporations using these for hiring decisions. Certainly it’s a fatuous claim that there are 16 kinds of people in the world, and knowing your ‘type’ will unlock some sacred understanding, but throwing MBTI and related tests in the same boat with astrology feels somewhere between disingenuous and lazy—there is valid and potentially useful data to plumb from drawing awareness to our tendencies and default settings, and in interrogating the contexts where we follow or deviate. from these tendencies.

Certainly, there is a whole marketing wing of this enterprise that oversimplifies and overstates the value of these instruments, in ways that are exploitative and gross, but dismissing them as appealing-but-invalid because they lack predictive value and are just easier to interpret than the ‘real’ psychometric is reductive.

(And fwiw, the MBTI and TJ 16 Personalities tools are NOT the same, as I’m sure the lawyers from both teams would scramble to point out).