Social Media and Political Violence

Issue 179: How social media fuels negativity, division, and hostility—and what we can all do about it

This week social media platforms are being blamed for inflaming divisions before—and after—Charlie Kirk’s murder.

After the conservative activist Charlie Kirk was fatally shot at a university rally in Utah last week, Spencer Cox, the state’s Republican governor, called social media companies a “cancer.”

Senator Chris Coons, a Democrat of Delaware, blamed the internet for “driving extremism in our country.”

President Trump, who helped found the Truth Social platform, also pointed fingers at social media on Monday and said the accused gunman had become “radicalized on the internet.”

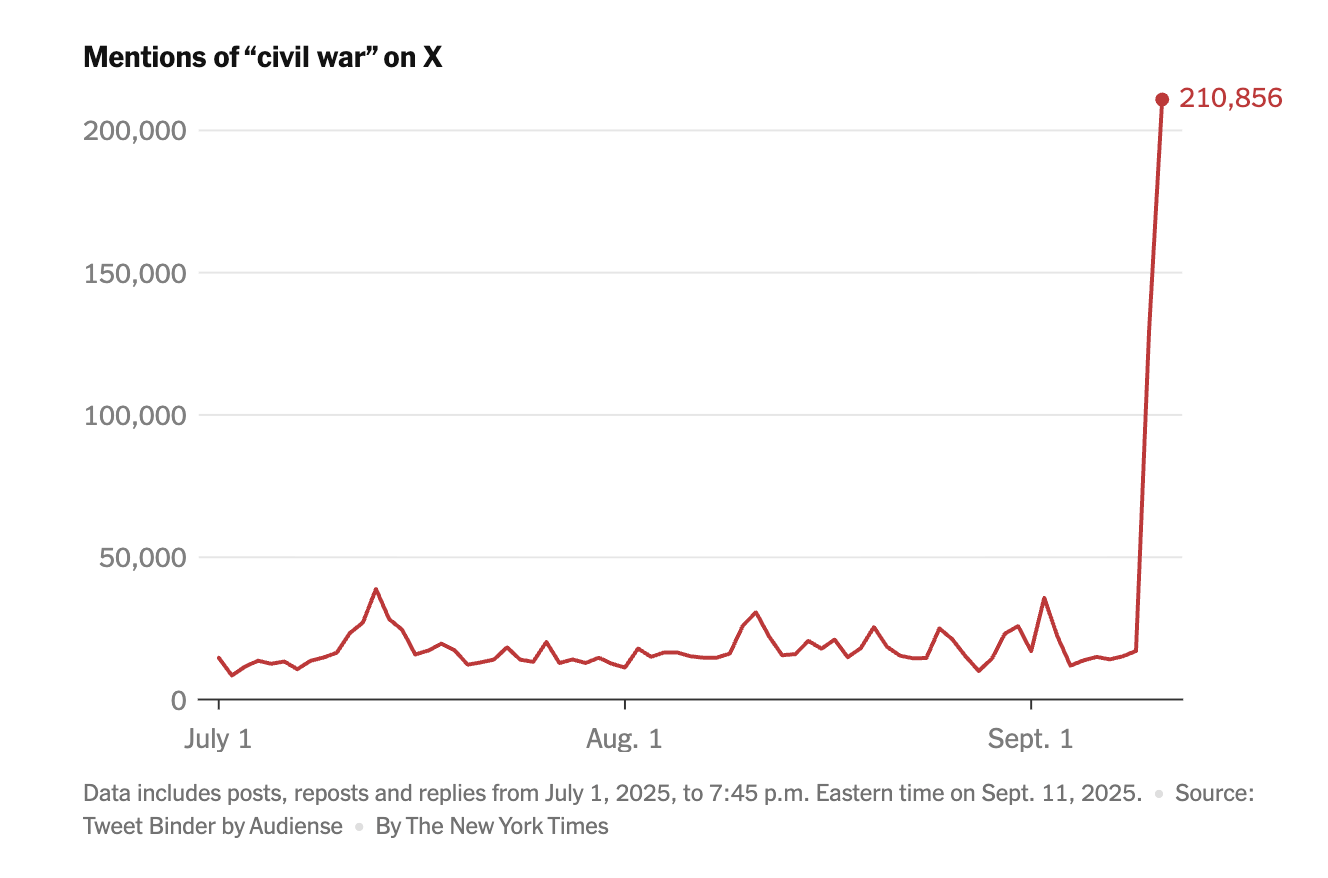

The aftermath of Mr. Kirk’s killing reveals how inflammatory and hateful online content has become. Countless people have been fired for their comments on social media, misinformation and conspiracy theories are running rampant, and the companies themselves are no longer even promising to solve it. Mentions of “civil war” have surged on X and Elon Musk seems committed to fanning the flames of conflict himself.

F…