INTERVIEW: Chris Chabris and Dan Simons on Why We Get Taken In and What We Can Do about It

Issue 76: Psychologist Christopher Chabris discusses his new book NOBODY'S FOOL on why people get taken in by hucksters, scam artists, and misinformation.

From phishing scams to Ponzi schemes, fraudulent science to fake art, chess cheaters to crypto hucksters, and marketers to magicians, our world brims with deception. In NOBODY’S FOOL: Why We Get Taken In and What We Can Do about It, psychologists Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris have a new book explaining how to avoid being taken in. They describe the key habits of thinking and reasoning that serve us well most of the time but make us vulnerable—like our tendency to accept what we see, stick to our commitments, and overvalue precision and consistency.

Each chapter in their book illustrates their new take on the science of deception, describing scams you’ve never heard of and shedding new light on some you have. Daniel and Christopher provide memorable maxims and practical tools you can use to spot deception before it’s too late. It also seem useful since Jay has been suckered into a Ponzi scheme as a teenage, lost $100 playing three-card monte in Stockholm, and accidentally shared misinformation on Facebook (it was a parody that seemed a little too real). So we were excited to interview them about the book.

Daniel and Christopher are fellow psychologists and we have following their work for years on attentional blindness and collective intelligence. In fact, we show samples of their research in our class. You can watch one here. Their first book The Invisible Gorilla: And Other Ways Our Intuitions Deceive Us was fantastic and we are excited to read the follow-up! It is in stores today and already a #1 bestseller on Amazon. So we strongly encourage you to buy a copy. Check out our interview with the two of them below:

What does your book teach us about social identity or group dynamics?

Nobody’s Fool is a book about why people fall for deceptions, from everyday misinformation and deceptive marketing claims, all the way up to life-changing frauds like Ponzi schemes and romance scams. Any act of deception is inherently social: it takes at least two for one to become a victim. As cognitive psychologists, though, we approached the question of why people fall for things through a different lens. We asked what cognitive habits (patterns of thinking and deciding) and what informational hooks (things about what we see that attract us and draw us in) are exploited by people who want to deceive us. For example, we tend to drop our guard when we're given exactly what we expected or predicted, and con artists take advantage of this habit. And we explain how our desire for potency (vast benefits from cheap interventions)—from the original 19th-century snake oil to some of the most hyped studies in 21st-century social science—leads us to accept implausible claims as solid when instead we should dig deeper.

Some of the big schemes we analyzed for the book have been characterized in social identity terms. Bernie Madoff’s fake hedge fund, for example, is sometimes interpreted as a simple case of affinity fraud: many of his victims already respected him because they were members of the same business or philanthropic circles he frequented. We look at this sort of trust as a kind of “commitment.” In our framework, commitment is the cognitive habit of holding an assumption so strongly that we don’t think to question or update our beliefs based on new information. When that assumption is wrong from the start, or becomes outdated later, it can lead us down a path toward being deceived (or deceiving ourselves further). Many of Madoff’s victims dismissed warnings from friends and advisors because they were certain he would never screw them. “Person X will never screw me” is just the type of commitment that can enable both a strong relationship (if X is a true friend who has your interests at heart) and a devastating betrayal, as it did here.

Often the simple act of getting a second opinion can help us avoid being conned. A wealthy French businessman was about to wire a large sum of money to scammers pretending to be his country’s Minister of Defense (long story …), but stopped at the last minute because a friend heard him discussing the transaction and immediately saw it as a scam. That outside view can make all the difference, and we should deliberately seek it before making big decisions.

What is the most important idea readers will learn from your book?

Scams and cons don’t just happen to “gullible people.” It’s tempting in hindsight, when you see a Netflix series or listen to a podcast about some outrageous fraud, to regard the victims as hapless dupes and to conclude that they should have seen all the signs, and that you would have spotted the plot a mile away yourself. While it’s true that some people probably are more vulnerable, especially people with cognitive impairment or people in stressful circumstances, there are scams lurking out there for everyone. In many of the examples we discuss, sophisticated, educated, intelligent people have been taken in. Just think of scientists who reviewed, accepted, published, and believed fabricated research when, in hindsight, the red flags were there. No one is immune, and believing you are makes you more susceptible!

Why did you write this book and how did writing it change you?

Our first book, “The Invisible Gorilla: How Our Intuitions Deceive Us,” came out in 2010—thirteen years ago! We knew shortly after then that we wanted to write another book, but it took a while for our ideas to coalesce into a coherent book. Meanwhile, scams and frauds kept multiplying, fueled by social media, greater worldwide connectivity, and what seems to us like an increasingly blurred boundary between legitimate and deceptive business practices. Once we started working on the book about three years ago, we had way more than enough material, unfortunately. In creating our “habits and hooks” framework for understanding deception, and seeing how many famous and obscure stories of deceit fit into it, we think we increased our skill at recognizing fraud and understanding how it really works. It also led us to re-examine some events from our own lives—a few of which are mentioned in the book—in which we might have been scammed, or narrowly avoided it.

What will readers find provocative or controversial about your book?

It doesn’t seem provocative or controversial to us, but the idea that falling for deception can be unpacked and understood from a cognitive point of view rather than reduced to a single concept (“trust,” “sociopathy,” “greed,” “too good to be true,” etc.) is the biggest contribution we tried to make. Nothing is as simple as we would like it to be, but we hope our framework helps readers as much as it helped us.

Do you have any practical advice for people who want to apply these ideas (e.g., three tips for the real world)?

Here are three simple life hacks that might save you from some of the most common scams around today:

Never buy a prepaid gift or debit card and then give the numbers to someone who calls you on the phone. No legitimate agency accepts payments this way, nor do they send the police to your house while simultaneously giving you one last chance to pay your alleged fine over the phone.

Never buy a product advertised as “rare” or “unique” from an advertisement. Fake art is mass-marketed, real art isn’t—but people have bought supposed Dalis and Picassos from late-night infomercials.

Don’t be afraid to ask more questions before making a big decision. Social pressures often work against being the asshole who asks for more information or raises doubts. Keep asking, or walk away, rather than get sucked into the vortex of influence.

You can purchase NOBODY’S FOOL here and follow Chris on Twitter here and his co-author Daniel here.

News and Updates

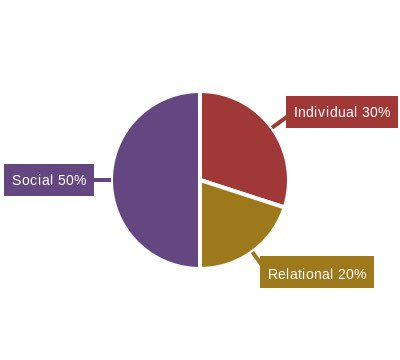

Do you tend to think of yourself and your identity socially, individually or relationally? Find out in our Identity Test for the WHO AM I CHALLENGE. Be sure to take the test yourself or share it with friends or co-workers in the next few weeks! We will share the overall results in a future newsletter.