INTERVIEW: Boldly Inclusive Leadership with Minette Norman

Issue 80: The science and practice of inclusive leadership, our APA Book Award, and a new review of our book from a psychiatrist.

Despite public commitments to diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging, many organizations struggle with leaders who lack the necessary skills for inclusive leadership. This week, we interviewed Minette Norman, a former Silicon Valley executive and author, about the essential insights at the intersection of leadership and psychology necessary for inclusion. Her first book, The Psychological Safety Playbook was a compilation of 25 proven moves to help leaders increase the psychological safety in their teams and to lead more powerfully by being more human.

In her newest book, THE BOLDLY INCLUSIVE LEADER: Transform Your Workplace (and the World) by Valuing the Differences Within, she underscores the importance of fostering a sense of belonging within every individual. She explains that team success arises in environments where safety encourages the sharing of diverse ideas and that innovation thrives best within collaborative efforts. Furthermore, Norman identifies empathy and compassion as pivotal strengths for effective leadership — notably, leaders' actions, words, rewards, and tolerances significantly mold organizational culture.

Given that we included sections on the power of psychological safety and inclusion in our own book, we thought it would be useful to share a perspective from someone who directly works and consults in the leadership space. Minette Norman discusses the underlying psychology behind concrete, inclusive leadership practices. Jay also wrote a blurb for her book, which we included below:

What does your book teach us about social identity or group dynamics?

As human beings, our affinity bias draws us to people who are most like us. That’s one of the reasons we hire, promote, and socialize with people who have the same backgrounds, personality styles, and ways of thinking. Unless we are deliberate about building an inclusive culture in our workplaces, we naturally form in-groups and out-groups, which means that there are always people who feel excluded and don’t feel they belong.

When you feel like an outsider, it’s hard to fully participate, to bring your “full self” to the group, and the group doesn’t benefit from all the forms of diversity that may be present. It’s lonely and often painful to feel like an outsider. Anyone who leads teams of humans has both the opportunity and responsibility to model inclusive behavior to dismantle the in-groups and out-groups.

What is the most important idea readers will learn from your book?

Leaders set the tone for their organizations not only with their own behavior but also with what they reward, tolerate, or overlook. Inclusive leadership is a practice, and every day provides a new opportunity to model inclusive behavior. Like any practice you may have in your life, you improve over time, but that doesn’t mean you don’t make mistakes or experience frustrations along the way. And when you commit to a practice, you don’t let the setbacks stop you from picking back up where you left off.

You learn from your successes and your failures along the way, and you try not to beat yourself up too hard when things don’t go well. When you commit to inclusive leadership, you incorporate the practice into your daily work. You don’t view it as something off to the side that you’ll pick up when you have extra time.

Why did you write this book and how did writing it change you?

After spending thirty years in the Silicon Valley software industry, twenty of those years leading teams, I realized how poorly we prepare people to lead others. My story was no different from most—I was promoted to manage a team early in my career with no preparation or training. I took on larger and larger global, multicultural teams and I realized that creating an inclusive, collaborative, and innovative team culture does not happen without deliberate effort. I saw how many people were ignored or marginalized for no reason except that they didn’t conform to the dominant group norms or backgrounds or experiences. I witnessed people holding back and not speaking up, even when they clearly had something important or innovative to contribute.

I decided to take everything I’d learned about leading groups and shape that into a book that could help others become better leaders. Writing the book made me acutely aware that being an inclusive leader does not only apply to a professional setting but also to our personal lives. I realized that it’s about being a good human being who cares about others and who realizes we are stronger together than we are as individuals. Writing the book also made me reflect on my own privilege throughout my life and how important it is for me to be not only an ally but an advocate, activist, and upstander for people who don’t have my privilege.

What will readers find provocative or controversial about your book?

Readers may be challenged by my book because I don’t offer a tidy three-step formula or memorable acronym that will turn them instantly into inclusive leaders. I suggest that embracing discomfort and being willing to be challenged is a necessary part of becoming an inclusive leader. The book might not be for everyone, but I’m optimistic it will find an important audience.

Do you have any practical advice for people who want to apply these ideas (e.g., three tips for the real world)?

Focus on becoming a better listener, which is an inclusive leaders’ superpower. When you truly listen with curiosity and the willingness to understand other people’s perspectives, people will see that you care about diverse points of view. Better listening also means managing your responses when you feel challenged or defensive.

Make sure everyone’s voices and ideas are welcome. This requires deliberately inviting dissenting viewpoints and responding positively when people are brave enough to speak up and challenge. Make sure you run your meetings in a way that everyone gets a chance to contribute and that no one is dominating the conversation.

Recognize empathy and compassion as strengths, and work on increasing your empathy for others by getting to know them on a human level. Resist the urge to believe that you should only talk about work-related topics at work—we don’t leave our emotions and humanity at home when we go to work. Be willing to spend the time it takes to get to know your staff members, colleagues, and leaders.

TODAY is the official launch of Minette’s book! You can check out Minette’s website here to download a sample chapter or order the book.

News and Updates

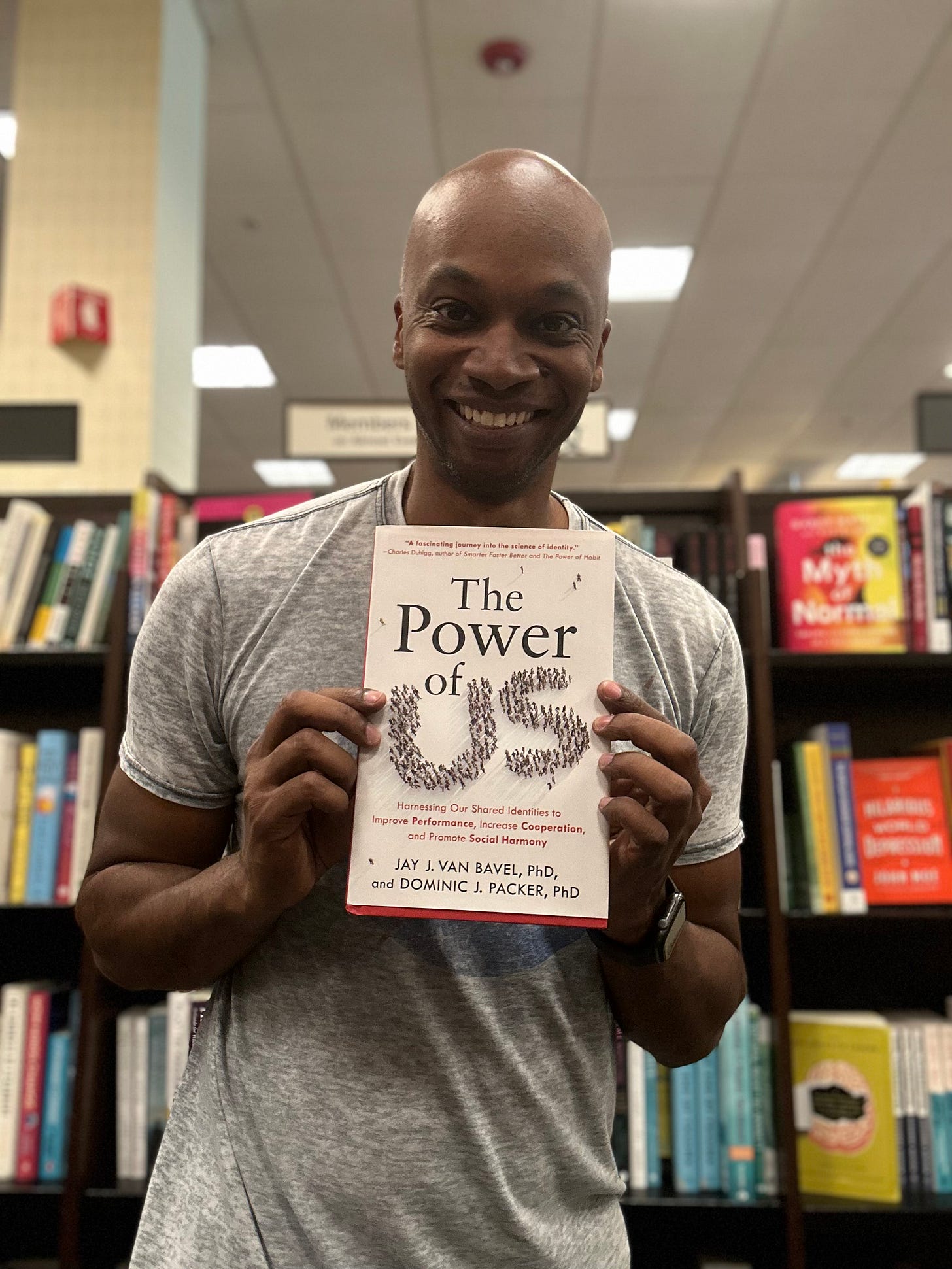

The very first person who read a draft of our book and sent comments (other than our Editor) was our friend Khalil Smith. Khalil is the Vice President, Inclusion, Diversity, & Engagement at Akamai Technologies and one of the deepest thinkers we know. At the time, he encouraged us to write a follow-up and we are soon going to start sharing some of those ideas in our newsletter this fall. So stay tuned! Khalil reads a TON of science books, and this week he spotted a copy of our book at his local Barnes & Noble in North Carolina while he was on the hunt for some brain candy.

We officially accepted the William James Book Award and gave an address summary THE POWER OF US at the 2023 American Psychological Association Conference in D.C. last week! Jay posted some photos on his Instagram. Here we are with President of the Society for General Psychology at APA, Dr. Claire Mehta. She was also on the book award committee and had to read 40 books. Thanks to Claire and the rest of the award committee for this incredible honor—we will include a summary of the award address in our next newsletter.

THE POWER OF US recently reviewed a detailed and thoughtful book review on Garth Kroeker’s psychiatry blog, where he nicely summarized some of our writing on fostering dissent:

The chapter on "fostering dissent" is especially insightful. The authors make the point that voicing a dissenting opinion within a group is socially costly. Even if the dissent is about an important logical or moral issue, the risk of dissenting can be to make other group members angry, and therefore threaten one's position as a group member. You risk being seen as disloyal or disrespectful. They argue that you have to really care about your group to be willing to voice dissent…

An approach to solving the dissent problem is to have a leadership structure or ethos in groups which encourages respectful disagreement, without fear of punishment or other consequences. Also it is vitally important, as a persuasive factor, to frame dissent or challenge with the group's long-term well-being in mind--to remind others of the group's core values, of the group's long-term interests, with a dissenting view intended to be a service to the group rather than merely a criticism.

Learn more about THE POWER OF US

If you like our newsletter, we encourage you to check out our award-winning book “The Power of Us: Harnessing Our Shared Identities to Improve Performance, Increase Cooperation, and Promote Social Harmony”. You can learn more about the book or order it from the links on our website (here or scan the QR code below). We keep the newsletter free, but are extremely grateful if you have a chance to purchase the book or buy it for a friend who wants to learn more about group psychology.

Catch up on the last one…

Most people misunderstand how social norms impact behavior, and last week’s newsletter isn’t really about dog poop (the original title had the word “dookie” in it). We use cleaning up after your dog as an example to illustrate that behavior change is more effective when we focus on desired behaviors, rather than what people are doing wrong.

Using social norms to clean up your community

We are in the dog days of summer and The Atlantic Monthly has dogs — well, more specifically, dog poop - on its mind. Writes Kelly Conaboy: A certain substance is enjoying a renaissance in New York City. In a time of scarcity, it is newly abundant. In a period of economic inflation, it is free and distributed so generously that it might even be on your …