Debunking Popular Psychology Myths: Why Most People Misunderstand Groupthink

We revisit the origins of groupthink and challenge one of the biggest myths about group dynamics

In May of 2021, the CIA’s Twitter account shared a photo of a curious artifact. A small silver coin shows a man with knife in his belt and brandishing a rifle, striding past a dead body lying prostrate on the sand. It includes the slogan: “No habra mas fin que la victoria”—there will be no end but victory.

The coin, we learn, was minted to commemorate what the CIA account dryly described as “an anticipated (but never realized) Bay of Pigs victory”.

Never realized, indeed. This military action, undertaken in 1961, was not only a foreign policy disaster for the United States and a major embarrassment for President John F. Kennedy, but it also become synonymous with one of the most misunderstood concepts in social and organizational psychology—groupthink.

The Bay of Pigs operation, planned by the CIA and authorized by John F. Kennedy’s fledgling administration, was an attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro’s communist regime by landing a group of roughly 1,400 expatriate Cuban fighters at the Bay of Pigs on the southern side of the island of Cuba. The fighters were immediately confronted by much larger Cuban military forces. Within four days, more than sixty of the US-supported fighters were killed and over 11 hundred were captured.

It was particularly striking how Kennedy’s brilliant team with Ivy-league pedigrees could fail this badly. The Bay of Pigs incident was such a disaster that when psychologist Irving Janis later developed his hugely influential theory of groupthink, he used the botched invasion as his archetypal example of the phenomenon.

According to Irving Janis, groupthink emerges in tightly knit groups when pressures for unanimity and conformity override individual members’ better judgment. A desire for group cohesion causes people to self-censor their doubts. Unexpressed, the absence of divergent views causes groups to become too confident in the wisdom of their choices.

Looking at Kennedy’s leadership team, Janis saw an overly-confident group of advisors among whom doubts about the mission were suppressed in the presence of a charismatic young president. Viewed through this lens, the commemorative coin seems to perfectly symbolize their groupthink—so assured were they of success, the administration had cast into silver an image of victory before a single fighter set foot on Cuban soil.

This is the groupthink origin story. Grounded in case-studies like the Bay of Pigs and escalation of the Vietnam War, the groupthink idea took off. Big time. The notion that conformity pressures cause groups to make poor decisions is now a common wisdom, routinely invoked to account for bad outcomes (and sometimes just choices that people disagree with).

It’s a powerful story.

Unfortunately, however, it is incomplete—and Janis’ analysis of events like the botched Bay of Pigs invasion is in need of significant revision. It turns out that things didn’t happen quite as we’ve always been told! And in the retelling, people have created a myth of groupthink.

By the 1990s, significantly more information about JFK’s team’s decision-making was available than had been accessible to Janis. Psychologist Roderick Kramer reanalyzed how JFK and his advisors had reasoned about the Bay of Pigs invasion and he came to radically different conclusions about what had actually happened.

Far from being overconfident, JFK had significant reservations about the operation. Planning for the invasion of Cuba had begun under the previous administration of Dwight Eisenhower. JFK felt that he had inherited an awkward and potentially dangerous “hot potato”.

Asked what he thought about “this damned invasion idea”, JFK said, “I think about it as little as possible.”

JFK and his team did make some faulty assumptions. Among them may have been placing too much faith in the military acumen of Eisenhower, under whom the operation had been conceived. As Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces, Eisenhower had led the successful invasion of Normandy in 1944, the most logistically complex military campaign in US history. Despite his misgivings, Kennedy believed in Eisenhower’s instincts.

More importantly, however, Kramer concluded that JFK’s team hadn’t fallen prey to groupthink at all—but instead to a phenomenon he called “politicothink”.

Rather than trying and failing to make optimal choices in terms of military strategy, JFK and his team were focused on the political consequences of their decisions. This focus led them to make choices they thought would minimize political risks even if they were not the best options for military success. They were too focused on public relations—which was the wrong goal.

This was a very different process than groupthink. And a very different type of leadership failure.

Richard Nixon, JFK’s opponent in the 1960 presidential election, played a key part in this political calculus. Nixon had been Eisenhower’s Vice-President and JFK realized that Nixon knew about the plans to invade and liberate Cuba from communism. He reasoned that if he cancelled the operation, Nixon would hammer him in public as indecisive and an irresolute defender of democracy. Despite his misgivings, he felt that the politics meant he had to move ahead with at least some kind of invasion/ Rather than being overconfident, JFK felt cornered politically.

Kramer’s reanalysis changes how we should think about groupthink. Certainly, poor group decisions can be produced by the desire to maintain cohesion. But bad decision-making can result just as well from other types of goals. Understanding the underlying root of the problem is critical to finding the right solution.

Sometimes a group may be trying to protect what they understand as their political interests. Sometimes they may be trying to maintain a certain positive reputation or perhaps reinforce boundaries between themselves and another group. In each case, a group is making choices that might be suboptimal for addressing important issues at hand, but that they believe will advance some other element of their agenda.

Rethinking Consensus & Strong Leadership

The central villain in the standard groupthink story is cohesion—groups that are too tightly-knit are thought to be most susceptible to poor decisions. The reality, however, seems to be more nuanced than that.

The myth of groupthink leads many people to assume that a longstanding team of collaborators should be especially vulnerable to groupthink. However, it is often groups of new acquaintances who suffer from groupthink. Eager to make a good impression, new coworkers are often the most hesitant to rock the boat or express too much criticism. They are playing a political game of their own—eager to fit in.

This is at odds with conventional wisdom and, indeed, the conclusions of some groupthink researchers. Testing the hypothesis that more cohesion would produce more groupthink, experimenters had observed that when group members were led to believe that they were similar and would like each other, they exhibited more of the symptoms of groupthink. However, these experiments usually took place with new groups, in which people were meeting each other for the first time.

But when researchers studied groups of longer-term friends, they found that friendship was associated with less, not more, groupthink. People in new groups have a strong desire to fit in and feel a sense of camaraderie, but this is different from real cohesion brought about by personal bonds developed over time in long term groups. It is these deeper relationships that allow for less posturing and more honesty.

Similarly, while bringing in outsiders (like expensive consultants) seems an obvious antidote to groupthink, it also has the potential to backfire. External perspectives can certainly reveal flaws in groups’ assumptions or provide new information, but this is only useful if groups engage with and incorporate those insights into their decisions. Unfortunately, research suggests that feeling that they are being observed by outsiders is often threatening and can create resistance rather than openness to new and different ideas.

Similarly, while overly-directive or charismatic leaders have long been blamed for creating the conditions for groupthink, this too warrants reconsideration. While we agree that leaders can certainly set the conditions for groupthink or politicothink, the solution for avoiding this problem is not less leadership, but more.

As we have written elsewhere:

“Strong and effective leadership is crucial for preventing groupthink. It takes leadership to set the terms of the discussion, create fair and inclusive parameters for disagreement, ensure criticism is shared, and establish healthy norms. Leaders have a responsibility to foster feelings of “psychological safety.”

Amy Edmondson, professor of leadership and management at Harvard Business School, has studied the importance of psychological safety in many groups, including cardiac surgical teams. At the time of one study, these teams were learning new procedures for operating on patients’ hearts, procedures which required perfectly-tuned coordination among surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, and technicians. With lives on the line, their ability to work together truly mattered, and it wasn’t necessarily made easy by differences in training, disciplinary assumptions, and status.

Edmondson found that the surgical teams whose members were comfortable speaking up were more successful at adopting the new procedures. Crucially, successful environments were fostered by team leaders who made sure their people understood the importance of their contribution to the mission. They were attentive to the potential for power disparities to disrupt communication. And they worked hard to attenuate status differences within their teams, careful to listen to and act on the suggestions of others.

A large study at Google (“Project Aristotle”) likewise found that psychological safety was critical to team success. After studying over a hundred groups for more than a year, their researchers concluded that group norms were the key to strong group performance–and teams that reported high levels of psychological safety were the most effective.

Psychological safety is often misunderstood to imply that we should create environments where people don’t critique each other. In fact, the opposite is required. People experience psychological safety when they know they are free to articulate contradictory opinions or divergent views because their group welcomes healthy debate and it won’t be held against them. Psychologically safe groups are places where people feel empowered to respectfully disagree with one another about the best ways to pursue their common goals.

Building the Right Norms

One of the lessons of the science of social identity is that people who identify strongly with their groups, who care and feel invested, typically conform more ardently to group norms. Sometimes these norms foster insularity, specifying in great detail what “we” believe about an issue or the only right way to think about things. But they do not have to.

It turns out that groups can form identities and find cohesion around just about anything. What seems like a threat to one group can, with the right leadership, be perceived as an opportunity in another.

Sometimes it is essential, for example, that a group embraces outside critique. Strong and effective leadership can help a team understand that outsider input is not a threat to their cohesion, but as a source of strength and an opportunity to grow. If this is genuine, it can become central to who we are: “We are the sort of people who seek all available information and learn from it.”

These are the conditions for making effective decisions in groups. It requires moving beyond the myth of groupthink and reaching a deeper understanding of what is motivating groups and how they reach decisions.

This is the third column in a series where we debunk popular psychology myths. You can read the first column that reinterprets the Bystander Effect (both the story of Kitty Genovese and the wrong impression that many have received from the original bystander studies) and the second column that discusses the Stanford Prison Experiment. We will debunk several other popular myths in the coming weeks.

News & Events

Jay recently hosted a weekend workshop on “The Power of Us: Lessons for Effective Leadership” for the Mongolian national chamber of commerce and industry’s member companies executives. We had a lot of fun and are planning around workshop in 2025!

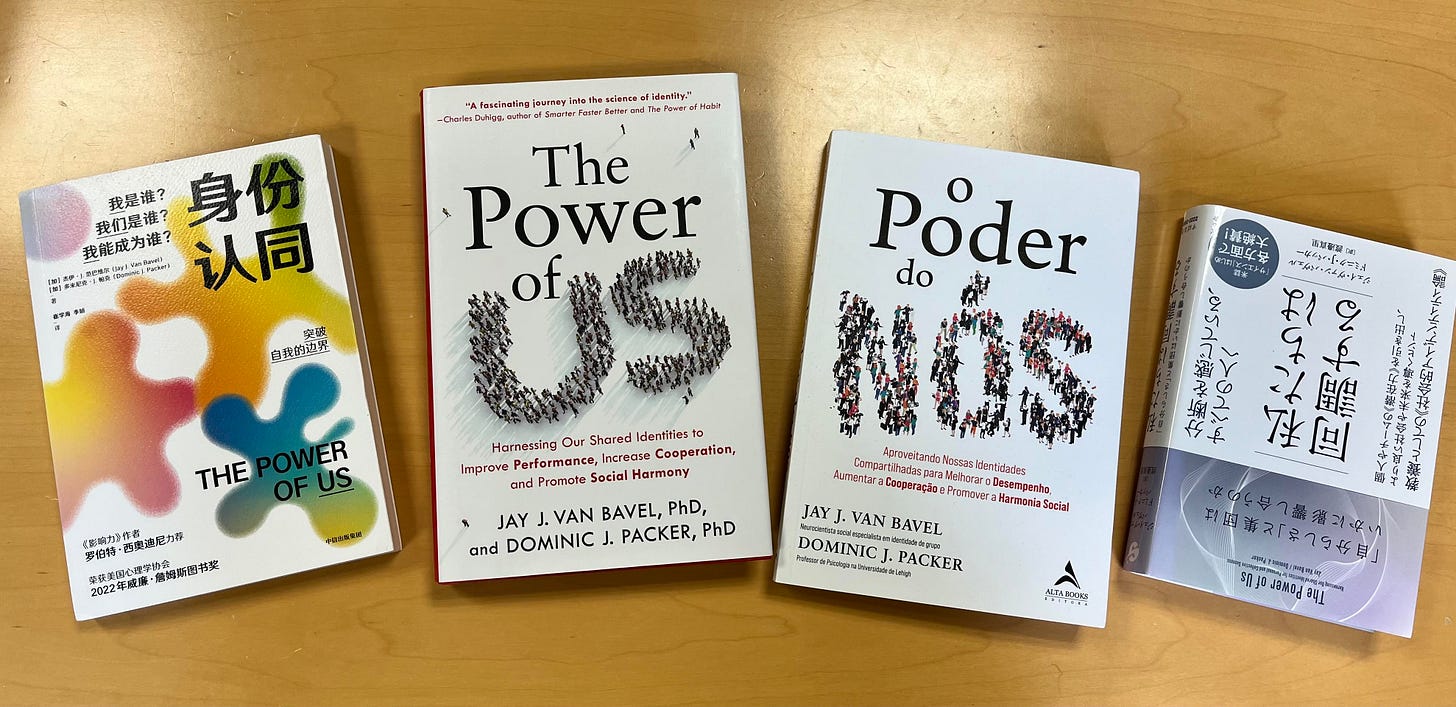

In addition to attending the workshop, they have translated the book into Mongolian. Our book is now available in 10 countries (you can see the full list here)—here are some of the examples sitting around our offices right now:

Catch up on the last one…

Last week’s newsletter was an interview with Hahrie Han about hew new book “UNDIVIDED” and how to build solidarity across divides

Cite as: https://doi.org/10.32388/substack.bjuq39 • PDF