Debunking Popular Psychology Myths: Revising The Bystander Effect

Our first column in a series debunking the biggest myths in the history of social psychology

The night of March 13, 1964, marked one of the darkest moments in the history of New York and the beginning of a myth that shaped how people saw the city—as well as human psychology—for decades.

For more than half an hour, 38 respectable citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a young woman named Kitty Genovese in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens. Twice the sound of their voices and the sudden glow of their bedroom lights interrupted him and frightened him off. Each time he returned, sought her out and stabbed her again. Not one person telephoned the police during the assault; one witness called after the woman was dead.

Exactly where the total of thirty-eight witnesses came from is not clear. But the notion that so many citizens could callously observe the stabbing and murder of a fellow human being without intervening triggered widespread outrage. People decried the decay of civilization and the degradation of life in New York City.

The story also struck a nerve with social psychologists John Darley (a professor at NYU) and Bibb Latané (a professor across the city at Columbia) who were working in New York City at the time. Based on the tragic story of Kitty Genovese, they developed and tested a hypothesis that they called “the bystander effect.” Their hypothesis was that the more bystanders there are in an emergency situation, the less likely any given person is to help. In their view, this might explain why people did nothing to help Kitty.

They theorized that there were at least two reasons why the presence of other people in an emergency can cause an individual not to act. First, it is not always clear what is and is not an emergency, and people often look to others to try to diagnose the situation. When you see that others are not reacting, you might assume that it is because they know it is not an emergency. This is a big problem if they reach the same conclusion by gauging your own lack of reaction. This is known as pluralistic ignorance—when no one knows what is going on but assumes that everyone else does.

Second, if people somehow overcome this mutual state of ignorance to recognize an emergency situation for what it is, they may still fail to act due to a diffusion of responsibility in which everyone assumes that someone else should or perhaps already has taken care of it.

Darley and Latané designed several clever laboratory experiments to test their idea. In one experiment, someone faked a seizure. In another, smoke began billowing under a door. They observed how participants responded to these crises when they were alone versus in the presence of other people who did nothing. Sure enough, people were less likely to help when there were others around than when they were alone. We highly recommend watching the video below to see the origin of the Bystander effect and vidid details about the studies.

Every time an event like this occurs (and they occur shockingly often), people—very rightly—ask why. How could people possibly just sit there, doing nothing to help while a fellow human being is in dire need of assistance? Although we note in our book that people do often, eventually, intervene, there are factors that seem to make this more or less likely.

But we now also know that neither the tale of Kitty Genovese nor the bystander effect is as straightforward as was long believed. They are simple stories that have been told and retold, often losing critical details in the retelling. They have become myths.

It turns out that some of the neighbors who heard Kitty Genovese’s cries for help the night of her death did intervene in one way or another. Although they were not sure what was happening, several shouted out of their windows and temporarily scared off the attacker. Some neighbors, including a boy who would later become a New York City police officer, reported calling the police during the attack. That the police never responded might have had something to do with the fact that there was no centralized 911 system in the United States until four years later. Before that there was no standardized system for receiving or responding to calls from the public.

An analysis of these events, however, suggests something far more nuanced:

"Psychology, unlike many of the other sciences, doesn't have a canon of uncontested facts," says Mark Levine, PhD, of the University of Exeter, who co-authored the American Psychologist article. "Because of this, psychology textbooks are not made up of facts students must learn. Instead, they are full of experiments and research techniques. Parables like the Kitty Genovese story serve to link the experiments to the real world. There is thus a strong incentive not to abandon the stories in the textbooks, even if the stories themselves are on shaky ground."

Just as Kitty Genovese’s tragic story is not as straightforward as it long appeared, not is the bystander effect itself. In particular, scholars and laypeople alike underestimate the influence that identities, and specifically shared identities, can play in people’s decisions to help.

In the early 2000s, Mark Levine and colleagues studied the dynamics of helping with English football fans. Some were asked to think about their identities as fans of a particular team - specifically, how much they loved Manchester United. Others were instead asked to think about their more general identity as fans of the game - as football fanatics.

Then, walking across the university campus to complete a second component of the study, they ran into an injured stranger. Like the Good Samaritan, did they stop to help? Or did they just walk on by?

Remarkably, whether they helped depended to a great extent on what type of shirt the distressed stranger was wearing. Sometimes he was in a Manchester United jersey, other times he sported the Liverpool colors (Manchester’s biggest rivals), and at other times he wore just an ordinary plain shirt.

Fans who had been asked to think about their love for Manchester United, the more parochial identity, were significantly more likely to help the stranger if he was wearing a Manchester United jersey compared to either of the other two shirts.

However, those fans who had thought about their love for football more generally behaved very differently. Having brought to mind this broader identity, they were just as as likely to help the stranger whether he was wearing a Liverpool or a Manchester United shirt. Notably, they remained quite unlikely to help a stranger in an unadorned shirt - someone with whom they still didn’t share an obvious allegiance.

Thus, as our identities shift, becoming more or less expansive, different people are included within the boundaries of our concern. These boundaries are not static, but depend on how we’re thinking about ourselves at particular moments.

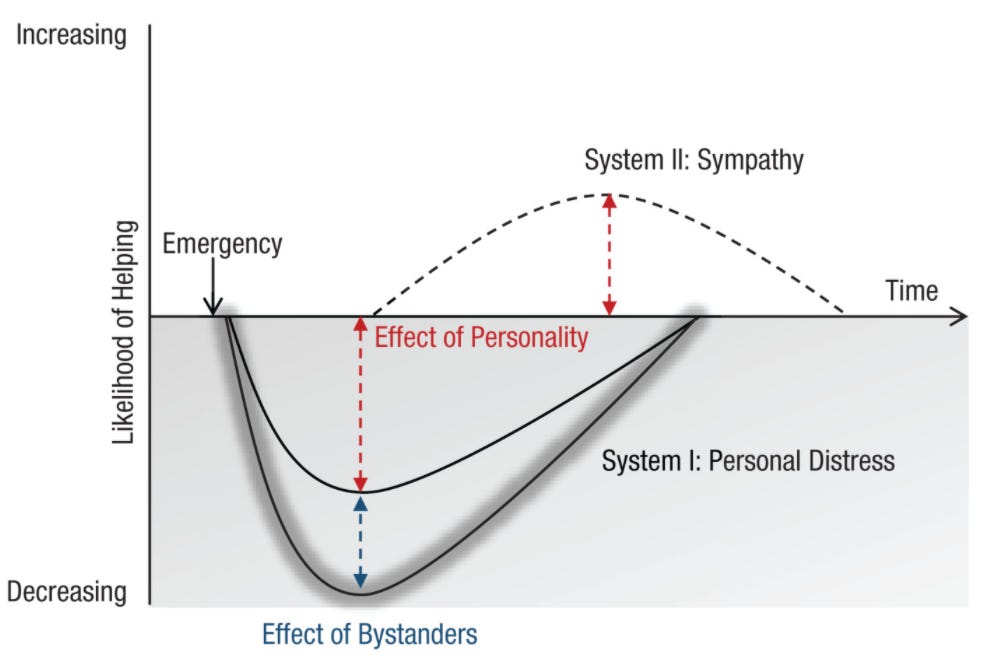

In 2018, Ruud Hortensius and Beatrice de Gelder proposed a new model of the bystander effect focused on how the brain responds during emergencies. They proposed that when people observe another person in need of help, two separate brain systems are activated. One system creates feelings of personal distress and produces freezing or avoidance responses—reactions that are not conducive to helping. The other system, which they claim tends to operate more slowly, creates feelings of sympathy, which can drive people to intervene.

According to their model, our immediate, instinctive reaction in emergencies is to freeze in a state of indecision or to run away if we can. These quick and unthinking responses can, however, be overcome if feelings of sympathy and concern for the victim, increased perhaps by a shared identity, are stronger and override them.

From this perspective, a particularly disturbing aspect of some media-reported examples of bystander apathy is the possibility that some people may record attacks on their phones. Stalling in indecision or trying to escape what one fears is dangerous are understandable, though hardly admirable responses. But recording an attack can be understood neither as freezing nor avoidance—and suggests a genuinely callous lack of sympathy that our models of bystander behavior do not really account for.

The bystander effect might give the inaccurate impression that helping is very rare in emergency situations. Recenter research has, however, dunked that myth as well. People actually do intervene in many, perhaps most, emergencies. One study, for example, examined surveillance camera footage of aggressive incidents in urban areas in the Netherlands, South Africa, and Britain. The researchers found that out of 219 public conflicts between two or more people, at least one observer intervened in 199 of them—that is, 91% of the time.

As you might expect, the more people who are around, the greater likelihood there is that someone will step forward, just by virtue of sheer numbers. But this doesn’t mean the chance of you intervening increases. It is important to understand this difference: The more people who are around, the better the chance that someone in a crowd will eventually notice something amiss and take action. But the probability of any given person in that situation doing something may still be quite low unless something triggers that person to help.

Returning to the issue of identity, it seems likely that people intervening in these studies might have been neighbors or at least have some common connection. This may also explain why the intervention rates were much higher than the studies with complete strangers in the lab.

Understanding why people fail to help assault victims in no way exonerates them. Rather, these insights should be used to train people how to intervene in moments of crisis. A recent review of relevant research highlights the importance of increasing awareness and encouraging bystanders to step up when someone is the target of sexual violence:

“Sadly, there’s very little evidence-based research on strategies to prevent or address sexual harassment. The best related research examines sexual assault on college campuses and in the military. That research shows that training bystanders how to recognize, intervene, and show empathy to targets of assault not only increases awareness and improves attitudes, but also encourages bystanders to disrupt assaults before they happen, and help survivors report and seek support after the fact.”

In fact, learning about the bystander effect has changed how we have reacted to sexual assault in the real world. As a graduate student, Jay once intervened during rush hour in a Toronto subway station when a man began assaulting a young woman. If you want to learn the whole story you can read our book and watch the short video we made on the bystander effect for our YouTube channel:

If you enjoyed this column, it is our first in a series debunking the biggest myths in the history of social psychology, which we will publish over the next couple of months. Subscribe to follow along as we set the record straight and bust some popular but erroneous myths about human behavior!

News and Updates

On September 18, Dom will deliver a keynote talk about the psychology of prosociality and cooperation at the Science of Philanthropy Initiative Conference in Indianapolis.

Catch up on the last one…

Last week, we recorded a live conversation with Jay and Dominic about free speech on college campuses through a podcast format. Listen to last week’s story below!

Free speech debate: Creating a more positive climate on college campuses

As a new school year begins, we’ve been reflecting on last year’s student protests and the discussions about free speech that continue to take place in the pubic sphere. We’ve been debating these issues privately with each other and with our colleagues, but we decided to talk live about it on a podcast and share it with our subscribers. You can listen to the full discussion here:

Cite as: https://doi.org/TK • PDF

Thanks for debunking the old bystander effect! It's important to scrutinize estabłished ideas, especially in social psychology.

Speaking of debunking and science, here is the Debunking Handbook 2020 by Lewandowski et al: https://www.climatechangecommunication.org/all/handbook/the-debunking-handbook-2020/

It says that effective debunking consists of first stating the facts in common language, them stating the myth only once, then explaining why it came to be, why it's wrong (create a cognitive dissonance) and lastly an explanation of the facts to fill the explanatory gap.

I'm looking forward to seeing more myths debunked! :)

The people who are recording the incident may be doing so, not out of callousness, but so that the offender can be prosecuted later, or because they believe that the offender will stop what he is doing when he notices it is being recorded.