Debunking Popular Psychology Myths: The Stanford Prison Experiment

Issue 136: Shining a light on evidence that was left out of the findings from the Stanford Prison Experiment.

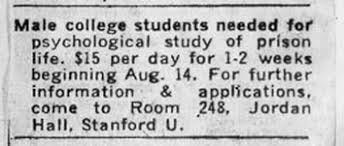

In the summer of 1971, one of the most famous experiments in the history of psychology was conducted in a 35-foot section of the Stanford Psychology Department basement. Each participant had responded to an advertisement in the local newspaper offering $15 per day to male students who wanted to participate with a "psychological study of prison life" that would last for one or two weeks in the basement of Jordan Hall.

After signing up to participate, eighteen healthy young men were randomly assigned to play the role of a prisoner or guard. Efforts were made to create as realistic a situation as possible. Before the prisoners arrived, the guards were provided with wooden batons, uniforms and mirrored sunglasses. This uniform was specifically to de-individuate them, and they were instructed to prevent prisoners from escaping.

The experiment effectively began when real Palo Alto police officers “arrested” the participant prisoners in their homes and charged them with robbery. They were brou…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Power of Us to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.