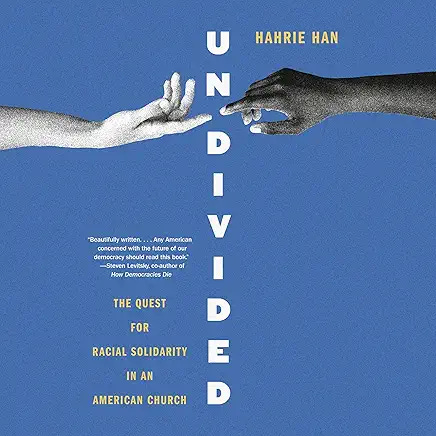

Building solidarity in an unlikely location: An Interview with Hahrie Han

Issue 137: In her new book "UNDIVIDED", political scientist Hahrie Han, shares lessons about how to bridge unlikely political divides

In 2016, even as Ohio helped deliver victory to presidential candidate Donald Trump, Cincinnati voters also passed a ballot initiative for universal preschool. What had convinced residents of this Midwestern, Rust Belt community to raise their own taxes to provide early childhood education focused on the poorest—and mostly Black—communities?

These are the sorts of fascinating questions that political scientist and director of the SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins university set out to answer question in her new book, Undivided: The Quest for Racial Solidarity in an American Church. We met Hahrie when we hosted a conference on polarization at the Agora Institute—she was also featured in a documentary we created on Protecting Democracy.

Hahrie’s book, Undivided, took her into the white-dominated evangelical megachurch Crossroads. The Pastor, Chuck Mingo, had delivered a sermon the prior year that set in motion a chain of surprising events. Raised in the Black church, Mingo felt called by God to combat racial injustice, and to do it through the church. The result was Undivided, a faith-based program designed to foster antiracism. The creators of Undivided believed that any effort to combat racial injustice must move beyond overcoming individual prejudices and get to the roots of the problem.

In Undivided, Hahrie chronicles the story of two men, one Black and one White, and two women, one Black and one White, whose lives were fundamentally altered by the program. As each of their journeys unfolded, they came to better understand one another and believe in the possibilities for racial solidarity in a moment of deep divisiveness in America. Her book shows what an undivided society might look like—and how we can help achieve it. As she notes:

Social transformation is not about finding extraordinary people and giving them extraordinary opportunities…Instead, it's about creating the social and structural conditions ordinary people need to take risks and connect their work to something larger than themselves.

What does your book teach us about social identity or group dynamics?

I have spent my career trying to understand the science of collective action. My research lab is called the P3 Lab because we are trying to understand how to make the participation of ordinary people possible, probable, and powerful--people have to be able to participate, they have to want to participate, and it has to matter. What are the practices we can use to pull people of all kinds off the sidelines and equip them to work with each other to realize the future they want?

Even with that background, working on this book taught me urgent lessons about the science of organizing, movements, and social change I didn’t know I needed to learn. In particular, it taught me what it takes to equip people to navigate some of the most intractable divides we have in America—race and faith—to keep them engaged in the work even when they faced backlash from their friends, families, workplaces, and churches, and how to connect their individual actions to a larger program of structural injustice.

And all this happened in the context of an evangelical megachurch—did you know that the top 9% of churches in American contain 50% of the churchgoing population? And that the average megachurch has been steadily growing, even as smaller churches die away? These churches are the growth edge of American Christianity and there is way more variability in them than most people understand.

What is the most important idea readers will learn from your book?

Social transformation—even in an evangelical megachurch—is not about finding extraordinary people and giving them extraordinary opportunities (e.g., find like-minded people and turn them into DEI warriors!) Instead, it's about creating the social and structural conditions ordinary people need to take risks and connect their work to something larger than themselves.

Why did you write this book and how did writing it change you?

Working on this book stretched my mind and my heart in ways I couldn’t have imagined. It introduced me to a world of people fighting for racial justice in one of the largest, white-dominant evangelical megachurches in America. When I first heard about this work in 2016, the campaign manager—who himself a veteran of many bitter political fights—told me it was “unlike anything” he had ever seen. He was right. The story surprised me at every turn—because of the way it demonstrated what becomes possible when we manifest the courage to fight for everyone’s dignity, the way it defied stereotypes about evangelicalism, and what it taught me about how communities like Cincinnati can overcome some of the most intractable divides we face in America.

The book traces the journey of four congregants at the Crossroads church—two men, one Black and one white, and two women, one Black and one white—who were all part of a racial justice program called Undivided in 2016. Each character became animated to take on the work of anti-racism, but then had to grapple with the inevitable backlash that came with the work during the Trump era, and what that meant for how they understood themselves, their faith, and their communities. None of the characters, nor the church, followed a linear path from complicity to justice. And the work remains fragile. But none of them came away unchanged—neither did I.

What will readers find provocative or controversial about your book?

Oh goodness, so much! In an effort to tell an authentic story, the book takes on topics that can sometimes be perceived as the third rail of both the political left (such as the DEI industry) and the political right (such as the racism that is built into aspects of white evangelicalism). Our one-dimensional political discourse often flattens the nuance needed to have real conversations about the ways in which the institutions we all inhabit—whether they are politically left or right, secular or religious, steeped in the language of DEI or not, faith-resistant or faith-filled—are flawed. Humans are imperfect, and so are the institutions we build. But sometimes we can't have authentic, complex conversations about the ways in which they are. This book does not shy away from that.

Do you have any practical advice for people who want to apply these ideas (e.g., three tips for the real world)?

I'm generally resistant to "listicles" or "tips" because I think they create the illusion that we can find shortcuts to the hard work of investing in each other's dignity. I think the truth is that if we take seriously the idea that every single person around us has equal dignity, then we each have a lot of complexity that we have to navigate about what that means about the choices we make. In many cases, that means we're making choices under conditions of uncertainty, or balancing ethical dilemmas to which there are no clear answers. So what can we do?

Most of my research focuses on social movements and community organizing. Organizers distinguish between "getting people to do a thing" (mobilizing) from "getting people to become the kind of people who do what needs to be done" (organizing). We live in a world in which the socio-political and economic systems we have are really good at "getting people to do a thing" but not as good at "getting people to become the kind of people who do what needs to be done."

The book tells the story of people who were part of a program, Undivided, that equipped them to become the kind of people who did what needs to be done when it comes to the work of racial justice. It wasn't easy and the answers weren't always clear. But if you wanted to apply the lessons of the book, the first thing would be to figure out what you need around yourself to become that kind of person--or, conversely, to either join or build a program that enables others to become those kind of people.

News and Updates

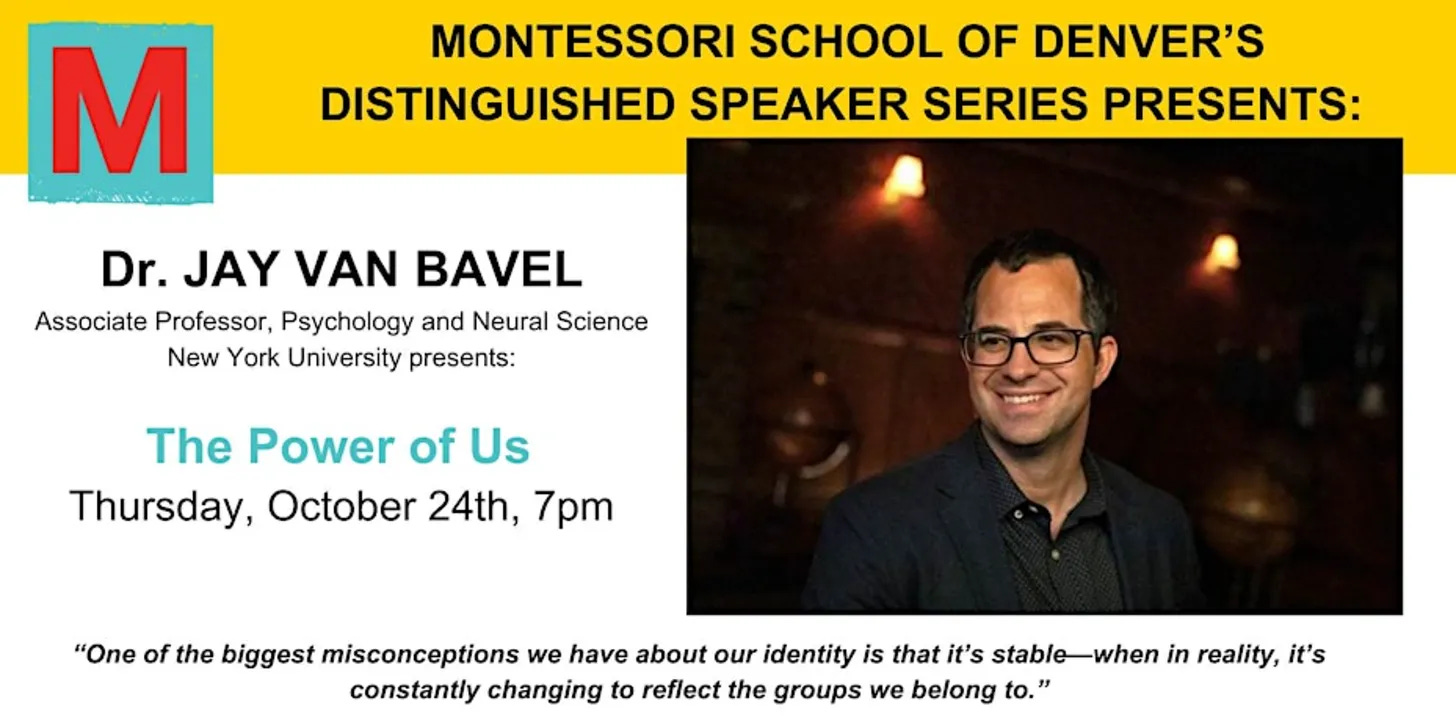

Podcast: Belonging can bring us together & pull us apart. Jay was on “The Connection” on WHYY radio last week to discuss how shared identities can lead to cooperation, sacrifice and generosity and also result in destructive, and hateful behavior. You can list to the hour-long discussion with Marty Moss-Coane here.

Event: Next month, Jay will be giving a keynote talk at the Montessori School of Denver’s campus about how educational leaders can use the power of shared identity to drive positive change success. You can register for the free event here! If you would like to collaborate with either Jay or Dominic on a speaking event or workshop, check out our website for more information.

Catch up on the last one…

Last week’s newsletter was one of our most popular columns ever! It was the second in a debunking popular psychology myths series, which will continue over the next few weeks.